A New Kind of Publishing

By Megan Hustad

The biggest professional challenge I’ve faced the last year is discovering that what was once my main means of attracting new author clients — the fact that I had first-hand knowledge of working with big-name New York publishers — was something I was no longer interested in promoting.

I still enjoyed working with authors who had big ambitions, and immensely so. That wasn’t the issue. I’d always made clear to prospective clients that while I’d do my damnedest to make their books critically laudable and commercially viable, I couldn’t make any promises as regards landing a big book deal. This was true even before big-name New York publishers began placing bigger bets on fewer books, and landing said book deal got harder.

No, the main problem was that clients who had come to me with their book proposals who did wind up with fancy book deals from weren’t all that happy with the experience they had with those publishers. This was partly a function of expectations; they’d anticipated feeling like being welcomed into a cozy house, given a seat at the table, feeling recognized as a whole person and affirmed as a talent, and instead they more often than not felt in the way, as if the publisher respected them (somewhat) but mainly wanted to get their book out into the world with as little interference from, or interaction with, them, the author of said book, as possible.

Note I’m not talking about reality here, but people’s feelings. This survey wraps some interesting hard numbers around those feelings, however.

Why was this happening? Several reasons. Publishing house employees are being asked to do more in less time, with fewer resources. There have been so many waves of layoffs, so much restructuring that satisfies some C-suite conception of streamlining but to the outside world — and to many of the company’s own employees — seems utterly pointless and enervating. This trend shows no signs of it reversing, especially with rumors that Amazon is putting the screws on. (Amazon has been trying to put U.S. publishers out of business for 20 years now, but that’s another story.)

It’s also that the rise of self-publishing has shifted the emotional dynamic and the business calculations. This happened slowly, then suddenly all at once. But the upshot is that self-publishing is no longer just for those who couldn’t get a book deal, but simply another alternative that makes sense for authors who want to keep more control of the project management aspects of publishing, more creative control, and more of a say in everything from price to distribution channels. (This Farnam Street podcast with the author Hugh Howey has an interesting take on that subject.)

So for authors who land a book deal with a major publishing house who wind up disappointed, they now have to wonder if they should have gone a different route. That’s an entirely new problem; there never was a respectable other way before.

In my view, and I’ve been banging on about this in private conversations for years now, is that publishers have to rethink who their customer is. Their customer isn’t really the end user, that is to say, readers. It’s authors. And if authors aren’t happy, they should be more worried about that than they are about Amazon.

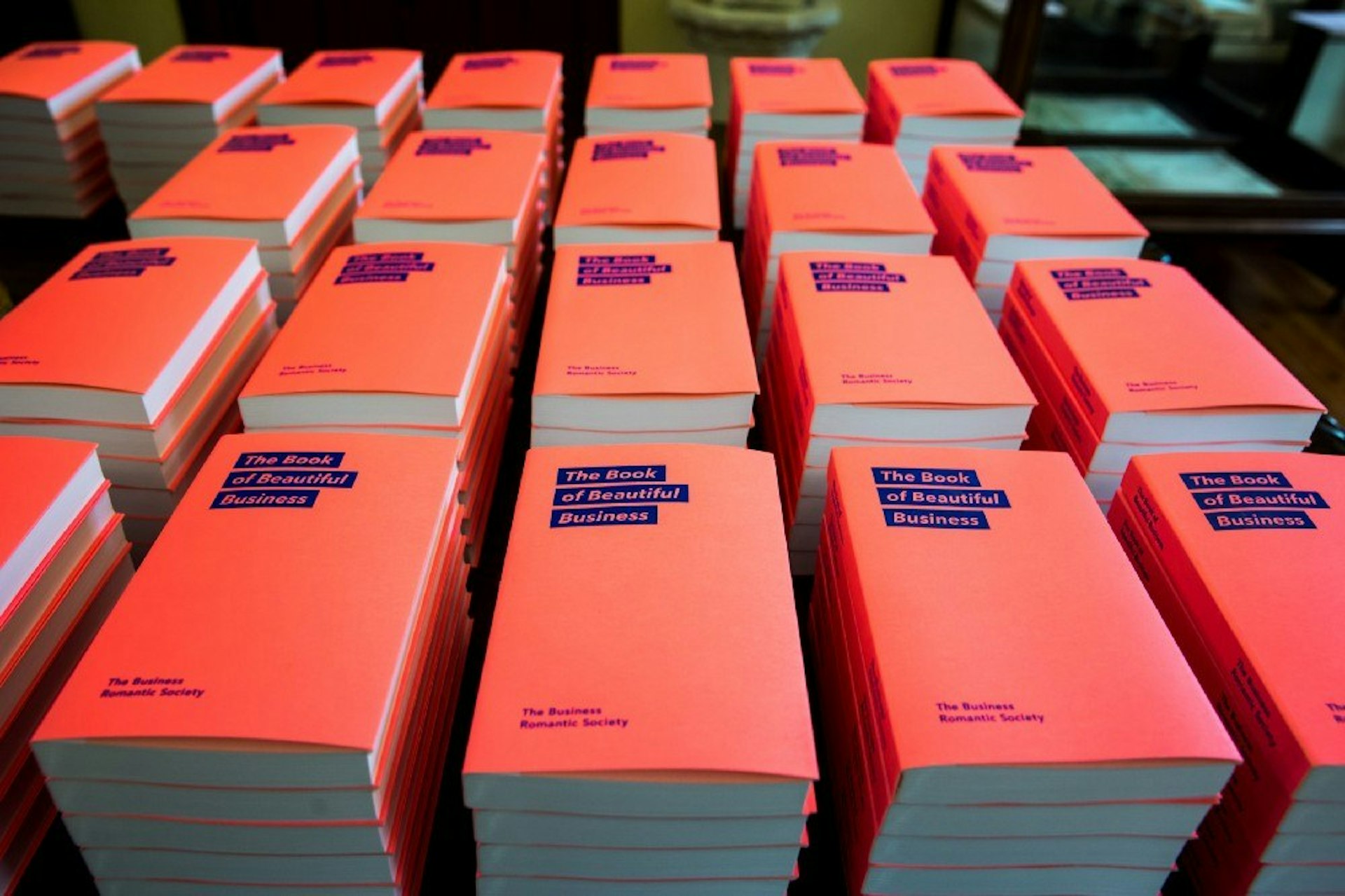

All this is a long way of prefacing why I was so glad to work on The Book of Beautiful Business these past six months, because for me it provided an opportunity to test a few theories on the new possibilities for books in an era when the options seem endless yet daunting, with so many more avenues for success but also bitter regret:

We need to stop referring to self-publishing. It’s a wildly inaccurate term. The reality today is that authors hire developmental editors, copy editors, graphic designers, typesetters, and marketing professionals to help them “self-publish.” Let’s just call what they’re doing publishing.

Email and cloud collaboration software are wonderful, life-changing products that we could exploit far more than we do, especially if we want to engage in work that has a global feel and process. For The Book of Beautiful Business, our editorial efforts were headquartered in New York, our layout designers were in Berlin, our printer and production manager in Riga, and our contributors wrote in from Cape Town to Stockholm. I had hoped to include a brilliant writer based in Shenzhen, but his schedule got in the way. Should there be a Vol 2, we’ll make it happen.

The freedom to set one’s own production schedules (all we knew was that the books had to be in Lisbon by Nov. 2nd), and when working as author/producer/managing editor — or all three at once — to be the main point of contact with your vendors, is invaluable. This is especially true when you’re working with remote teams in different time zones.

Anthologies should be more playful. Traditionally anthologies meant you had +/- 20 contributors who have all been given the same assignment, and who submitted pieces of roughly equal length. Nothing wrong with that, of course, but it didn’t feel right for a community like the House, which is diverse in terms of where people lived and worked, diverse in native languages spoken, and most importantly, wonderfully varied in discipline and practice. An anthology today should reflect that diversity with pieces that vary greatly in length, tone, style, even in terms of commitment to “the cause,” whatever that might be.

It’s important and fun to surface the names of people who contribute to a book project, and not only credit them in acknowledgments which few people outside the industry read anyway. Bring those experts and collaborators front and center. Run credits on the copyright page, perhaps. This transparency demystifies the process and also helps authors who are not well-connected, or who don’t have an idea of whom to turn to for help, with some solid leads. You could do a Google search for this help, of course. Or you could just flip open a book that’s been produced in a way you appreciate, and see who they credit.

I’ll close this post with a list of links to people who worked on The Book, so you can check out their work.

Garvin Hirt of FLOK Design

Livonia Print, with a special shout-out to our endlessly patient Production Manager Silga Čerpinska

our copyeditor Sarah Sarai

Eva Talmadge, proofreader and more

And of course Tim Leberecht, who came up with this crazy idea in the first place, and suggested I come along for the ride. I’m grateful.