What Do Employers Owe Their Workers Now?

“An employer only owes an employee two things,” began a comment on a post by Charlie Warzel late last month. “A safe working environment and the agreed-upon wages at or above the legal minimum.”

Whether you agree with that belief is a question worth exploring. On the surface, sure, it sounds right: Workers are not slaves. We’re free to enter into contracts, to negotiate those contracts, to leave if we decide the terms aren’t good enough for us. But, as Warzel points out, this is both the status quo and an “unnecessarily cold way to approach our work lives.”

“Why, exactly,” Warzel asks, “should our culture aspire to such a calculating and extractive means of employer/employee relations? What if employers...choose to imagine something better?”

What would “something better” look like? Let’s talk about the ways that workers and employers everywhere are figuring that out, and discuss more at this week’s Living Room Session.

In this issue:

Paying your dues—is it a scam?

The tyranny of productivity

Benjamin Pring on not expecting rapid change

Elizabeth Cotton on the darker side of working life

No more fake nine-to-fives

What started the conversation between Charlie Warzel and his commenters last month was the disconnect between “agreed-upon” hours and what’s actually expected of employees in white-collar work. Showing up at nine a.m., leaving promptly at five, having the weekends to yourself—that might be fine for anyone who wants to be “mediocre” at their job, but if an employee wants to keep that job, or to advance in their career, the expectation is that they’ll work far beyond the agreed-upon forty hours every week.

The reason that workers have accepted this bad bargain for so long—apart from a culture where overwork has long been the norm—is that, as Warzel explains, it came with the promise of some payoff: Eventually, that exhausted worker will get promoted, or earn some security, or reach retirement. “Paying your dues” is supposed to be worth it in the end.

But employees are increasingly pushing back against that argument. Younger workers, especially, are questioning whether the promise of dues-paying is really just a scam. What if that hoped-for career stability never comes? What if employees are submitting to the pressure to work so much not for the sake of their futures, as Warzel asks, but only to enrich a set of shareholders?

Disillusionment with work is nothing new, but clearly the pandemic has catalyzed a huge amount of social change. Essential workers, in some places, are bargaining for better treatment. In the office—or working from home—white-collar workers have had both the time and distance to reflect on the companies they spend their lives with. Things like insincerity and double standards that they may have been too busy to pay attention to before have become harder to ignore.

Social movements, too, have made everything feel different. Connie Wang, executive editor of Refinery 29, credits last year’s resurgence of Black Lives Matter with much of the change in workplace culture that we’re witnessing now:

“Corporations from L’Oréal to Amazon opened the door to criticism by aligning themselves with Black lives, when Black employees’ own experiences said something very different about these corporations’ cultures. Across the business world, the massive delta between external words and internal actions became too hypocritical to bear.”

While previous generations saw problems in the world of work from the perspective of the individual (whom the employer owes nothing but a safe working environment and agreed-upon wage), today’s workforce, Wang explains, sees those same problems as macroeconomic, linked to the economy, to geopolitics, to the environment. “When they see a problem, they are more likely to question the entire system.” And to fight for their right to work only from nine to five.

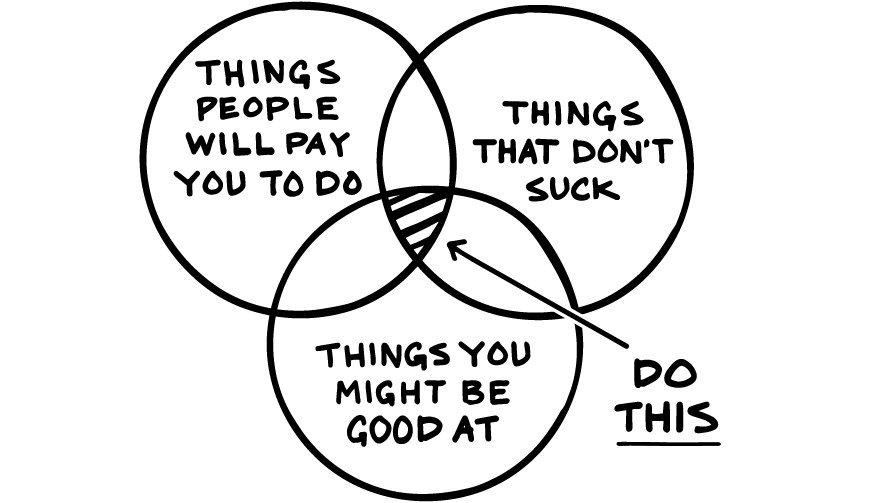

Graphic by Scott Galloway

Don’t expect change overnight

Benjamin Pring, VP of thought leadership and manging director at Cognizant's Center for the Future of Work, says not so fast. Last week, when we sat down with him to talk about how work will continue to transform over the next few years, he cautioned us against hoping for rapid change:

“You always have to balance the forces of change against the forces of inertia. And the forces of inertia...are attached to fundamental, deep, economic, social, human qualities that really, frankly, don’t change that quickly. We still have to meet our deadlines, make our boss happy, make our client happy, we still have to pay the bills.”

Pring characterizes the pandemic not as a catalyst of revolution, but—for those of us who are privileged to work mainly on a screen—as something more like a holiday. There’s been an upside to not having to get dressed in the morning, not having to commute—and, like a holiday, it cannot last.

“The reality is that we live in a very competitive, late-stage Western capitalist marketplace. A very aggressive marketplace. And those are facts of life.”

What the pandemic has changed, he says, is the way we think about our work lives, and how intentional we are about deciding where to work, and for whom. Before it started, white-collar workers still followed the same lifelong pattern: move to a big city after college, work for a big-name company, pay those dues. But now, as he puts it, “we’ve got an opportunity to think about work, and about how individually, corporately, and as a society, we want things to work.”

So maybe the pandemic has sparked more change than Pring initially allowed. “The hybrid model is now becoming very conventional,” he told us, giving as one example a team where employees come together in person every Wednesday and Thursday, with the rest of the week left to workers to fill their time as needed, be it answering email, talking to clients on the phone, or doing the “heads-down” work of writing messages or code.

Which may lead to the biggest change of all: The rise of smaller cities. New York, Berlin, and Stockholm will remain expensive, but with more focus on working remotely, Pring argues, more young people may decide to start their careers in places where they can live more comfortably. Instead of commuting for an hour-plus to an office in Midtown Manhattan from a cramped apartment at the outer edge of Brooklyn, they may seek out places like Portland, Maine.

“Cities are not dead. They’re just going to be different cities, because the underlying dynamics of wealth and opportunity in places like New York and London are out of reach now, for the next generation of people who can work in different ways, in more intentional ways, on different platforms, or with different tools and technologies.”

Let’s hope those new platforms, tools, and technologies for work will make work a better experience for us all.

Optimize the sector, not the person

Cal Newport argues in the New Yorker this month that productivity itself is not the demon that the anti-productivity movement has made it out to be. The real problem, he suggests, is the focus on the individual instead of on the workplace—or the sector—as a whole: “I’m convinced that the solution to the justified exhaustion felt by so many in modern knowledge work can be found in part by relocating the obligation to optimize production away from the individual and back toward systems.”

What would optimizing an entire sector look like? Slack and Google Hangouts over email? How about a group of workers banding together to say no?

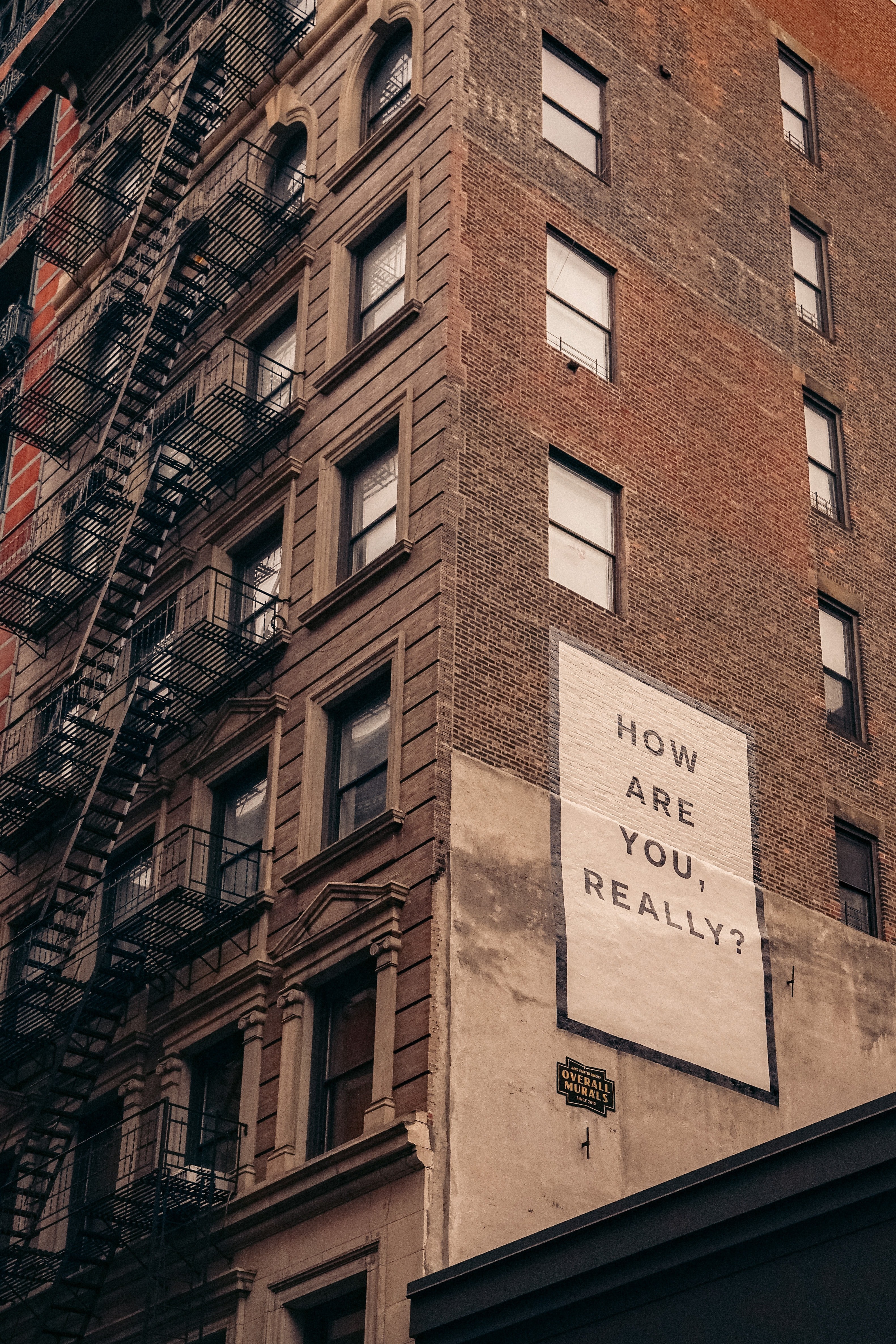

Photo by Hanson Lu

Where it gets ugly is where we are now

“In the end you have to laugh. It’s all completely mad.”

“I leave work feeling uncomfortable.”

“I feel pretty stuck right now.”

These are some of the responses from surveys that Elizabeth Cotton, a writer and educator in the field of mental health and work, published in The Future of Therapy this year. With a background in international employment relations and work with the Global Union Federations in the global south, Cotton draws parallels from her previous work to the moment of development we’re in right now.

In preparation for our Living Room Session this Thursday, we sat down with her to learn about her view of this “back to work” moment. First, she explained to us, it means acknowledging where to begin:

“Acknowledging this moment means really engaging with the darker side of working life, and any human interactions, and any humanizing processes. What you find is not just love, you also find hate, and you find anger and resentment. Developmental processes are slow and complicated, they move backwards and forwards, and often, they are very painful.”

Before rushing into business-as-usual, falling for the false haven of efficiency, Cotton urges us to give in and turn toward the kind of love that is real:

“It’s about things like intimacy, about knowing that you both love and hate the people around you. And that you are dependent on people, which is a horrible realization that our narcissistic cultures—they just don’t want to even go there. We want to be superhuman, we want to be self-sufficient, we want to be independent. But it completely crushes the life of actually having a relationship with the people who are around you, not some idealized version of it. So in terms of business, I do think it is love, real love. It’s concrete love, in an itchy-scratchy way.

“One of the things I learned in the trade union world that I’m now relearning in the space of mental health is that you never know who is going to care for you. In a situation of crisis, particularly at work, so many of us are facing crises around discrimination, bullying, harassment. You never quite know who’s going to be the person who saves you. And it probably isn’t the person that’s paid to do it. It’s usually not the person who is closest to you, or who you think is really funny. There’s this kind of really wonderful humanizing process that can be part of work trauma, which is that you learn to value people as human beings, not as kind of objects or commodities. You learn to appreciate that all human beings have the capacity to really care for each other.”

In the face of this exhausted workforce coming back (or not), increased wage inequalities, particularly for essential workers and those with caregiving roles (affecting a majority of women, as the latest Global Wage Report by the International Labor Organization shows), and culturally ingrained toxic work environments, Cotton criticizes the current hype over tech-based well-being and mental health programs that, all too often, don’t scratch the surface of mindfulness-as-a-benefit.

“The problem with services like chatbots, online therapies, and programs towards well-being and mental health at work is that it compounds that injustice. It says the problem is you, you need to change your attitude, you need to change your cognitions, you need to change your behavior. It’s all about neurolinguistic programming. These tools can be quite powerful, but they’re in no way a substitute for creating the conditions where people are able to constructively relate to each other.”

The “uberization” of mental health services is what she calls the current phenomenon, which prevents one’s actual capacity of developing as a person and as a leader. Rather than downloading the next diagnostics app that will tell you which box you’re fitting in, Cotton asks us to get engaged with one another, to form relationships, and to start to listen, listen, listen, rather than jumping ahead to the solution. Then comes the real homework, for every one of us who desires to keep working and to grow:

“Don’t think that your experience is universalized support—people are very genuinely diverse and the world is not what we think it looks like from our computer screens. You have to look at research, which talks about discrimination or mental health, talk to experts, go to events that you wouldn’t normally go to and that are uncomfortable for you. In addition, staying committed to the process is key: this means having more conversations than you would want, more delegation than you would want, relinquishing control, and having the humility that you may not understand the situation. One of the toughest things about mental health is that the person that you need to talk to, to understand what’s going on, is the person least likely to talk to you. The people that are in the most distress will find it the most difficult to show you their vulnerability, and they will make it hard on you, and they might be angry with you and they might shout at you and they might resent you. There’s no fantasies, it’s real. And you wouldn’t always choose these to be the people that you’re with, but they are.”

15 questions

Do you feel stuck, or are you just tired?

What do you want to go back to?

What do you not want to go back to?

How has your view of “having a career” changed in the last year?

9-to-5, 996, or no more at all?

Can you take a break without feeling guilty?

Are you using well-being apps regularly?

How have they impacted your daily routines?

How do you measure your productivity?

How do you measure the impact of your work?

When do you not multitask?

Do you have a bullshit job?

How much of your work is based on what you want?

Do you love what you do?

How much?