Can Victoria’s Secret Become a Beautiful Brand?

After Victoria’s Secret was spun off by its owner, L Brands, and in light of declining business, the lingerie behemoth announced on June 16th that it was replacing its iconic “Angels” (models who embodied the unlikely combination of six-pack abs and size-C bustlines) with the “VS Collective,” a group of seven women that includes athlete and LGBTQ+ activist Megan Rapinoe, South Sudanese refugee Adut Akech, and size-14 body advocate Paloma Elsesser. To call this a rebrand is an understatement: After years of selling what was essentially a male ideal of what women should look like, the company has made an about-face, promoting inclusivity instead of fantasy. Some welcomed the move (“better late than never”); some smelled purpose-washing (“as flimsy as a polyester thong”). The debate polarized the House team, too, which is why we decided to share two conflicting opinions with you. It’s complicated. Or is it?

Yay! Let’s not write off brands as cynical

Tim Leberecht

My first reaction was: Victoria’s Secret as the steward of feminism and diversity? Sounds like a bad joke from a late-night show. Sure, the brand may have finally retired its “Angels,” but a pivot toward becoming “woke”? Too little, too late.

Victoria’s Secret has been tarnished for pretty much every possible leadership misconduct and workplace scandal you can think of: from misogyny to bullying and sexual harassment to cultural appropriation.

In short: The Victoria’s Secret brand is toxic, and if you endorse it, it will make you toxic, too.

But this is precisely what presents the opportunity for transformation, and I give the members of the new VS Collective credit for signing up for this (almost) impossible task. They could have had it much easier by becoming brand ambassadors for, say, Patagonia or ARMEDANGELS, or another undisputedly “good” brand. But Victoria’s Secret? It’s like stepping right into the lion’s den, where the tensions between capitalist forces and social change, between putting lipstick on a pig and a genuine desire for something new, become almost unbearable, and perhaps irreconcilable.

Just to get this out of the way: Selling out is not the issue. Someone like former soccer star and now-entrepreneur Megan Rapinoe deserves every single cent she’s making in this new role (which is not just a testimonial but also gives her and the other VS Collective members say over business decisions). Her compensation will likely not compensate for the gender pay gap she experienced as a professional athlete.

A space for the still-waking among the woke

Becoming a “woke brand” can be easily dismissed as a cynical maneuver, but do intentions matter more than outcomes, even if these are unintended consequences? How can social change occur if not through the avenues of mainstream business? Can we stage a revolution without guillotining those who are not on the right side of history (yet)?

The words of writer Anand Giridharadas come to mind: “Is there space among the woke for the still-waking?”

That question, to me, is at the heart of the Victoria’s Secret case. Whatever we think of its motives, Victoria’s Secret has the power to create the space for the still-waking among the woke. In the best case, its brand pivot will bring issues to mainstream America (and thus, the world) that can help us overcome some of the polarization caused by the culture wars and widen the playing field for a whole generation.

Victoria’s Secret may no longer be in tune with the zeitgeist, but it still has tremendous influence on millions of lives. In North America, as of January 2021, there were almost a thousand Victoria’s Secret stores, with each store generating about $4.5 million annually on average. Victoria’s Secret is inclusive in that it is affordable for large swaths of the population, and it can shift the perceptions and well-being of girls and women, for better or for worse. Moreover, it can enable parents to view their children in a new way. If a brand like Victoria’s Secret embraces fluid identities, perhaps it will inspire them to do so, too? As an intergenerational brand, even just a slight moving of the goalposts can make a difference.

All that being said, a look at the Victoria’s Secret website will quickly tell you that actions don’t match words yet, and that the company still has a lot of work to do to credibly live up to its new purpose. But at least it has one now. It can be ridiculed and even despised, but with this move it is showing a new vulnerability. It may be exposed as fraud or ensure new relevance—time will tell—but it is a journey worth acknowledging.

Of course purpose-driven brands are marketing, after all. The goal remains to sell more products. But a brand like Dove shows that it is possible to be commercially minded and change social norms at the same time. Like Victoria’s Secret, Dove sold a beauty product, in this case, soap. In 2012, Victoria’s Secret and Dove even campaigned against each other, with Dove launching its “Real Beauty” campaign (anointed by PRWeek “the best U.S. marketing campaign of the past 20 years”) as a direct response to Victoria’s Secret’s “Love my body.” Evidently, Dove was almost a decade ahead, and it has successfully practiced—not devoid of missteps and criticism—what Victoria’s Secret is attempting now: to use its marketing power to assert a far less narrow ideal of beauty.

Not a loved brand, but a lovable one?

Earlier this year, I wrote about the difference between a loved brand and a lovable one, citing urbanism professor Michael Benedikt:

“What makes (some) ugly things lovable is the hope for transformation, or the knowledge that it is imminent. The duckling we know will become a swan is not really ugly.”

Victoria’s Secret may not be a loved brand, but it can definitely still become a lovable brand.

Every brand transformation can be mocked as window dressing in the beginning, and the jury over how genuine it is is always out. Every action taken always seems too little, too late. And yet, if the alternative is to not even try, to not even begin, then I’d vote for giving brands—with Victoria’s Secret being the most recent example—a chance.

Beautiful business is not a retreat, it’s a constant crisis, a perennial conflict. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but it is never an absolute vantage point. To be beautiful is to be ugly. Otherwise, it’s just cosmetics.

Nay: Phony marketing won’t change anything

Eva Talmadge

In its press release, Victoria’s Secret announced that it was on a journey to become “the world’s leading advocate for women.” Coming from a company notorious for an internal culture of misogyny, bullying, and harassment—exposed last year in an investigation by the New York Times—where women who complained about an executive’s harassment faced retaliation, that’s quite a journey. As recently as 2018, the chief marketing officer of Victoria’s Secret’s parent company said he didn’t think the brand should include “transsexuals”—an offensive term—in its annual fashion show. And among the many revelations that followed the arrest of Jeffrey Epstein on sex-trafficking charges in 2019, one of the most explosive (though perhaps also the least surprising) was that Epstein had posed as a modeling recruiter for Victoria’s Secret—with company-owner Les Wexner’s full awareness—since the mid-1990s. As Vanessa Friedman writes in the New York Times:

“On this side of the #MeToo and recent social justice movements, the imagery that drove Victoria’s Secret to record profits and viewership—and made its favored models part of pop culture—seems not just retrograde but practically unimaginable, like coming upon some lost civilization buried beneath a dusty mound of garter belts and thigh-highs.”

Victoria’s Secret is the company that launched Pink, a product line that featured lacy underwear emblazoned with the words “I Dare You,” whose target audience includes children: girls and women ages 13 to 22. Created as a place where men could shop comfortably for lingerie, the brand has always been about what men want, famous for doing zero market research into customer preferences, and coming up with ideas for new merchandise in meetings that consisted exclusively of men.

To date, the new version of Victoria’s Secret has not expanded its size range, or responded to questions about how they’ll actively support women’s and LGBTQ+ organizations. With a market share that has shrunk from 32 percent in 2015 to just 19 percent as of December 2020, the rebrand seems less like a swerve toward advocacy and more like desperation, following a massive change in consumer preferences that made their “Angels” seem outdated years ago.

So call me skeptical. Victoria’s Secret sells cheap and trashy polyester garbage. The world would be a better place if they weren’t in it. Calling their new batch of brand ambassadors a “collective” does not change the decades of pimp culture, objectification, and softcore porn that they’ve legitimized as something women are supposed to want.

Everything has to change

Can brands transform? Many companies have updated their appearance in recent years, from the elongation of the Warner Bros. logo to match the golden ratio to the new custom font for PBS. Starbucks dropped “coffee” from its name, and Dunkin’ has famously dropped “donuts.” Bigger changes have happened at Burberry, which was once banned from U.K. clubs for being considered gang wear, and at McDonald’s, whose locations now look like Starbucks, and which now serves salads. But do any of these rebrands mean real change?

It’s easy to put a rainbow on your logo to show that you’re celebrating Pride Month, or hang a banner supporting #BLM. (Woke-washing and rainbow-washing have been credibly called lazy, if not downright hypocritical.) But to truly change a company, something fundamental has to shift, and that kind of change does not come quickly. “It lives in the collective hearts and habits of people and their shared perception of ‘how things are done around here,’” argue Bryan Walker and Sarah A. Soule. “To harness people’s full, lasting commitment, they must feel a deep desire, and even responsibility, to change.

The problem is everywhere

Sexual harassment across the fashion industry is rampant, from the abuse of garment workers at Gap and H&M to the assault of models by photographers and agents. While the problems at Victoria’s Secret may be orders of magnitude greater than those at other companies, they’re certainly not the only brand with a sexist reputation. Lululemon founder Chip Wilson was forced to step down after making offensive comments about his customers in 2013. In 2018, Lululemon CEO Laurent Potdevin resigned after an affair with a former employee caused a scandal that revealed a company-wide toxic culture. And in 2020 alone, Amazon, Bloomberg, Disney, Fox News, Goldman Sachs, Google, Hearst, Johnson & Johnson, McDonald’s, Oracle, Pinterest, and Warner Bros. all faced lawsuits over gender discrimination and harassment. These are not the kinds of problems that a more diverse marketing scheme is going to fix.

So are rainbows!

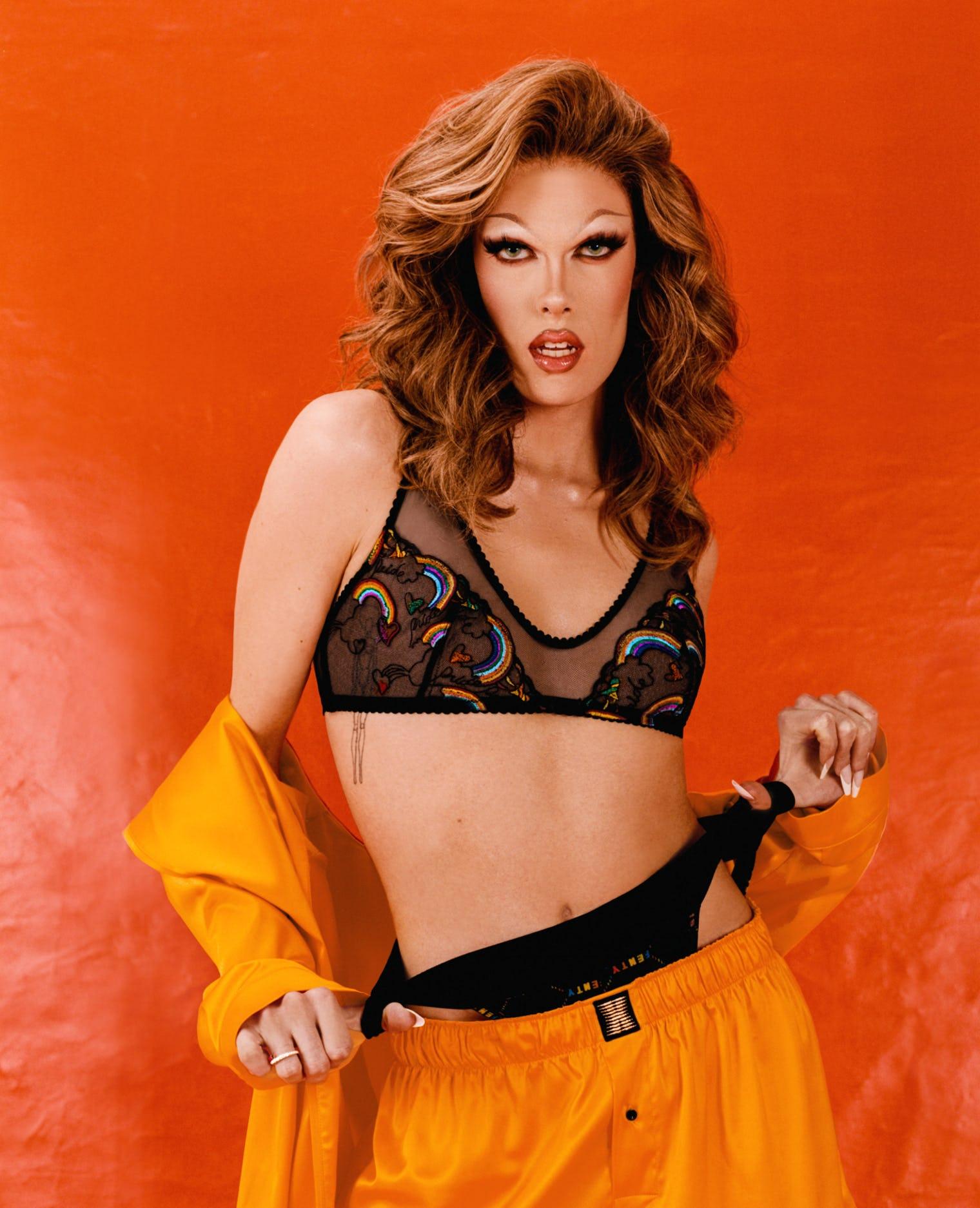

On a happier note, gender-neutral fashion is spreading its wings. Savage X Fenty, the clothing line started by pop icon Rihanna, introduced its first-ever pride collection this month, featuring rainbow-print lingerie and silk boxer shorts meant for people of all genders, abilities, and sizes—from XS to XXXL. And they’re not alone: A new generation of underwear brands, including Play Out Apparel, TomboyX, and Urbody, are leading the way in a growing market for genderless clothes. According to a new study on Gen Z buying preferences, only 44 percent of respondents said they always bought clothes that matched the gender assigned to them at birth.

15 questions

- Too little, too late?

- Or just in time?

- Would you wear it?

- Would you gift it?

- Do you believe any of this?

- Are you cynical?

- Or hopeful for change?

- Which brand lost your loyalty?

- Which brand did you give a second chance?

- Can you think of a brand you buy just because of its purpose?

- Does your personal brand need a rebrand?

- What do people say about you when you’re not in the room?

- Whom would you ask to be your brand ambassador?

- What is your purpose?

- When did you change?

GIGI Goode for Savage X Fenty's Pride Campaign