Decode Thyself : Self-Discovery Through DNA and the “Myth of Genes”

By Roberto Veronese

About 2400 years ago, before entering the temple of Apollo in Delphi, Greece, worshippers read an inscription known as one of the Delphic maxims: Gnōthi seauton — “Know thyself.”

The maxim has been in use for centuries with different interpretations such as knowing our place in relation to the divine, or to the great order of things. Pragmatically, “know thyself” urges exploration into our qualities, our strengths, and weaknesses, our potential, and limitations, what’s unique about each one of us, and also what’s common to us all.

Being aware of who we are as individuals is arguably crucial for achieving happiness in life. It might help us pursue the life we were born for — if such a concept were possible.

Fast forward to today, the full mapping of the human genome — completed just 17 years ago — has become a fundamental resource to understand our biology and associate a broad range of human predispositions with variations in our genetic code. However, a key question regarding the relationship between genomics and the knowledge of the self and its nature seems to be still unexplored.

Can the interpretation of our genetic makeup help us “know thyself”

In the third book of the Republic, the philosopher Plato used the “myth of metals” to illustrate his preferred type of society based on aristocracy. In his view, or more accurately in Socrates’s view, aristocracy should be grounded on meritocracy although not quite meritocracy on the basis of demonstrated achievements. Each individual would be born with inclinations, propensities, and potential that had to be identified early in life and then fostered through suitable environments and education. Therefore, according to such a view, merit would be determined first and foremost according to inborn qualities.

The myth was elaborated through metaphors. Different metals would be mixed into our soul: gold for rulers, silver for government functionaries, and brass or iron for farmers and craftspeople.

The “myth of metals” argued that regardless of their social class, someone born with a silver or bronze soul was not allowed to govern since such a role was accessible only to those with gold in their soul. In such a hypothetical society, everyone would find their right place based on their inborn inclinations — their nature, some would say — and their appropriate cultivation.

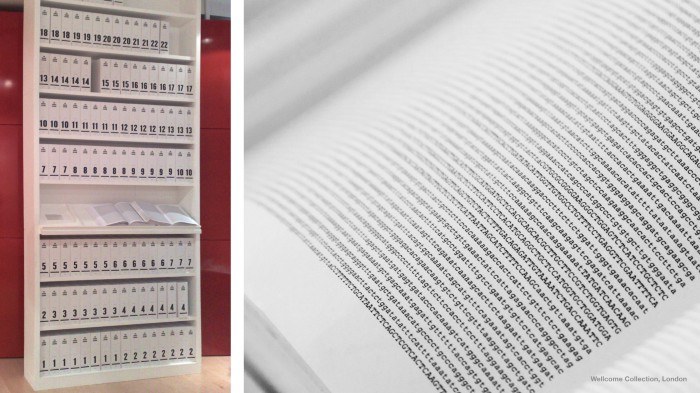

There is no gold, silver, or brass in the way we read our genome. There is a sequence of letters. The letters stand for the building blocks of our DNA strands. Each one of us has a slightly different sequence of letters, and therefore comes with a slightly different set of biological instructions. However, the genetic makeup of all humans is 99.9% the same, and just 0.1% of our DNA is responsible for our diversities — among other factors.

The analogy between genetics and the “myth of metals” is merely a provocation that we could call the “myth of genes.” However, concerns and beliefs in genetic determinism are present in popular culture (e.g. the iconic movie Gattaca, Kanye West’s genetic programming among other examples). Moreover, some researchers suggest views that may be interpreted as supportive of mainstream ideas, based on a series of studies and their controversial conclusions. Let’s try to unpack this matter.

The growing knowledge of our genome has sparked thousands of research studies with the goal of correlating the small but crucial differences in our genetic sequences with the traits and conditions that we manifest as individuals, from the color of our eyes to the development of a disease at some point in life. Of course, the reliability of those correlations hinges on the quality and quantity of the data available, which are steadily increasing. As such, so is their statistical value.

Most people are familiar with correlations used to determine people’s ethnicity. In fact, over 20 million people — in the US alone — purchased an ancestry test out of curiosity about their origin and wish to be matched with potential relatives. Apparently, the category is slowing down in light of value concerns among consumers (e.g. cultural identity is not about genetics) as well as privacy issues.

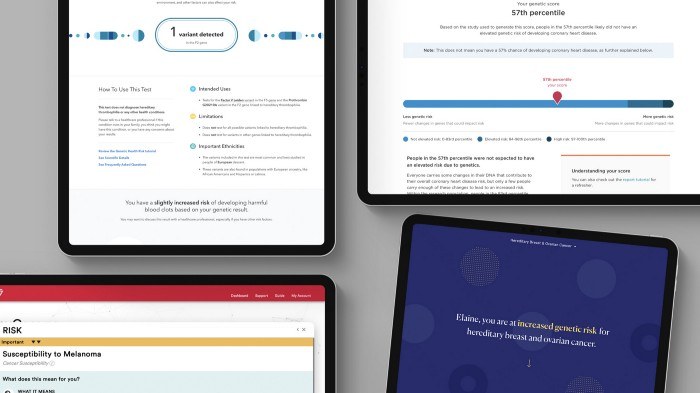

However, there’s no doubt that the most valuable and actionable use of genomics is in healthcare as it provides indications about the potential risk that an individual may develop a condition (e.g. cardiovascular disease or a type of cancer) in their lifetime.

The clinical interpretation of genetic information is helping identify people at risk for inherited conditions and determine preventative care pathways. It also allows individuals to screen for conditions they might pass down to their children, especially when both parents are carriers. Last but not least, pharmacogenomics aims to predict a patient’s likely response to drug therapies, reducing inefficient and expensive “trial and error.”

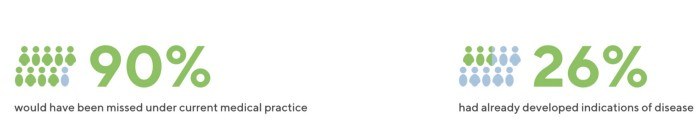

A clinical example is offered by the Healthy Nevada Project, an initiative launched two years ago — in its second phase — to sequence and screen 250,000 Nevada residents for three well-known genetic conditions: familial hypercholesterolemia, hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, and Lynch syndrome.

To date, this large population study identified a significant number of individuals (1.26% of the population) whose risk for developing those specific conditions would have been missed by existing medical practice. Among those carrying a pathogenic variant, 26% had already developed indications of the disease. Indeed, being a carrier of pathogenic variants portends a substantial risk for the disease, and the age of first diagnosis is statistically earlier for carriers. Therefore, rapid detection and intervention can reduce morbidity and mortality.

Genetics is also predictive of several physical traits, including eye color and height. For example, height is 80% heritable. That’s not surprising when we look at our family, although genetic variations sometimes produce unexpected results.

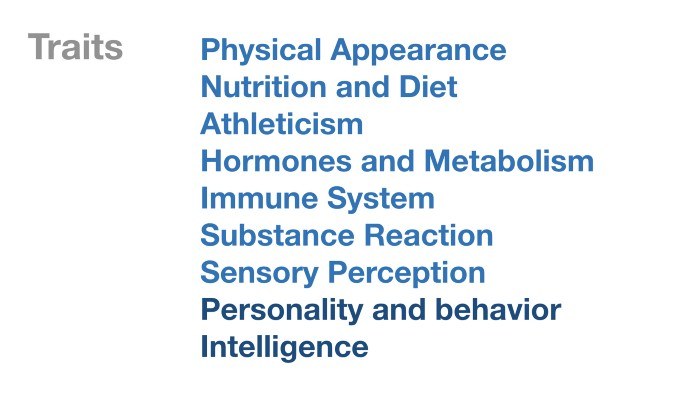

A number of genome-wide association studies identified the correlation between personality traits, behavioral traits, cognitive skills, and even academic achievement — qualities such as grit, extraversion, curiosity, impulsivity, ease of learning, or doing math — with specific variations in the sequence of the human genome. Research found that if you consider all the differences between people in cognitive ability, about half of those distinctions is somewhat heritable. That’s a very interesting finding — among others on the subject — although it may induce hasty conclusions.

For example, we can all recall times when we felt something came “naturally” to us or it didn’t, almost as if we weren’t “made for that.” By analogy, one may easily think that so-called “natural talents” or the lack of a predisposition may be written in our genetic code after all, just like our propensity to grow tall or have brown eyes. If our height is 80% heritable, why not also our intelligence and personality? It’s an understandable assumption but also a grand simplification, and a controversial one. There’s an obvious difference between a physical trait and a cognitive ability. They are not apples to apples. Also, a vast amount of research shows that non-genetic factors can affect some traits more decisively than others.

Complex traits like intelligence (of any type) are known to be polygenic — in other words, influenced by multiple genes. Some researchers advanced the theory that complex traits are even more than polygenic and in fact omnigenic, meaning that essentially, all of our genetic code determines, as a whole, a certain predisposition. The matter is indeed complicated and what is being reported in the media doesn’t always help our understanding.

Researchers are developing polygenic scores to consider multiple genetic factors at once and estimate — for instance — the probability for a high IQ or the likelihood that an individual will be “capable, persistent, and conscientious” enough to complete their schooling years. Reminder: all scores are probabilistic, not deterministic.

For example, this study, among others, does not show that educational attainment and intelligence are determined by a person’s genes. However, that study among others argues that our genes may have an influence, although limited, in our ability to get a school degree. At the same time, we should keep in mind that correlation does not equal causation or the explanation of a phenomenon.

This is all interesting — you may think — but what about our opening question? Can the interpretation of our genetic makeup help us “know ourselves”? Can it contribute to the process of understanding — and perhaps, accepting — our identity, personality, and potential? Can it tell us what type of life or career we’d be most successful at pursuing?

For sure, DNA improved the understanding of our biology to prevent diseases and determine personalized medical treatments. In that sense, the big book of our DNA is certainly increasing our knowledge of ourselves. However, based on what we know today, decoding our genetic makeup alone will likely not answer the big questions of our identity, personality, and potential.

Given the probabilistic value of genomics, our DNA’s utility is greater when its application is predictive, and not introspective or self-reflective.

From a predictive standpoint, the value of the genome should be even greater when we consider the youngest among us. Besides the preventative clinical applications, a few researchers claim that knowing the probability for a certain type of personality, mental disorder, or cognitive difficulty might help parents and educators inform and adjust their nurturing approach toward very young children. There are not only major disagreements on the subject in the scientific community but also understandable concerns among the public.

Most of the common fears surrounding genetics regard the possibility of predicting human traits and capabilities on a mere genetic basis, and eventually, allowing their “programming.” Somehow like the “myth of metals,” the “myth of genes” envisions a hypothetical scenario where genes — which could be programmed — would determine the possibilities of each individual and their place in society. Concerns tend to fall into the theme of humans acting in arenas where their interventions may have unintended and unpleasant consequences — gene therapies, gene editing, embryo selection in IVF based on genetic analysis, and potential unethical applications. The unease with the progress in genomics outside its recreational (see ancestry) and clinical applications (disease prevention) is ultimately about inequality, as it would lead to less diverse, even less equal, and less free human societies.

If one is worried about inequality, the possible misuse of genetics should not be the first and foremost concern. There is plenty of work to do in society toward addressing inequalities as is. As a second counterpoint, the scientific community tends to agree that our genetic makeup is just one of the factors that contribute to making us who we grow to be. Not everything in our genome finds its expression during our lifetime. Statistically, the influence of genes is not stronger than the effect of environmental factors, including the vast number of social determinants.

On that note, and to return to where we started, it seems fair to conclude that understanding ourselves will continue to be the result of a life journey, not the result of a genetic test.