The Life-Centered Economy: Past, Present, and Future

“The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” — Milton Friedman

Does the quote above feel jarring to you?

It does to us too—an indication of just how far our values have shifted since the quote was used to headline a 1970 article by Milton Friedman in the New York Times.

Friedman, of course, was an ardent advocate of free-wheeling, free-market capitalism. Regarded as a leader of the Chicago School of monetary economics, he wrote several acclaimed books—including Capitalism and Freedom in 1962—and in 1976 received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

Along with fellow economists F. A. Hayek and James Buchanan, Friedman is generally considered one of the architects of twentieth-century neoliberalism, the ideology behind such controversial policies as fiscal austerity, trickle-down economics, deregulation, privatization, and reduced government spending.

In the last half-century or so, neoliberalism has shown itself to be not only less economically dynamic than the preceding period of Keynesian welfare capitalism (which had double the growth rates) but has ushered in an era of banking scams, collapses—we’ve seen two go down in the last few days—and corporate tax evasion, recessions and inequality, and rampant populist nationalism.

In more recent times, neoliberalism has been increasingly seen as the cause of our current “polycrisis”—a 1970s term resurrected by economist Adam Tooze to describe the interplay between the COVID-19 pandemic, the invasion of Ukraine, and the energy, cost-of-living, and climate crises.

In short neoliberalism’s myopic and greedy grasping for profits over everything else is what we might call—without too much hyperbole—the Death-Centered Economy. It is, frankly speaking, the most persistent ideological barrier to what the world needs: a more sustainable, inclusive, and spiritual planet. Or in other words, a more Life-Centered Economy.

A Brief History of the Life-Centered Economy

The concept of a Life-Centered Economy isn’t new. Even as Friedman and Co. were busy constructing their growth-obsessed paradigm, other economists and philosophers were warning of its inherent dangers and positing alternatives.

In 1970, an international team of researchers at the MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) studied the implications of continued worldwide growth, feeding data into the World3 computer model to simulate consequences and discovering that the then-current rates of economic and population growth couldn’t last beyond 2100—if that long.

Their findings were published in the 1972 book, The Limits to Growth, which stated that it might be possible to create a society in which man can live indefinitely on earth, but only “if he imposes limits on himself and his production of material goods to achieve a state of global equilibrium with population and production in carefully selected balance.”

Degrowth as a term was coined in 1972 by Austrian-French social philosopher André Gorz. And a year later, in 1973, Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess came up with the phrase Deep Ecology to describe the global grassroots environmental movement that was emerging to redress the deficiencies of technology-based ecology.

By the 1980s ecological economics was well underway, with Chilean eco-thinker and ‘barefoot economist’ Artur Manfred Max Neef proclaiming that “no economic interest, under any circumstance, can be above the reverence for life,” and publishing a taxonomy of fundamental human needs that still seem more relevant than ever today: subsistence, protection, affection, understanding, participation, recreation, creation, identity, and freedom.

David Korten, a former professor at Harvard Business School, was also sufficiently inspired by The Limits to Growth—as well as the work of microbiologist Dr. Mae Wan Ho and evolutionary ecologist Dr. Elisabet Sahtouris on organisms as intelligent self-organizing living systems—to devote his life to political activism and displacing what he describes the “suicide economy” in favor of a life-serving earth economy.

His books, which include 1995’s When Corporations Rule the World and 2000’s The Post-Corporate World: Life After Capitalism are sober but scathing critiques of the system, and his 2021 paper Ecological Civilization: From Emergency to Emergence, proposes a reimagined socio-ecological model for the twenty-first century that reconnects people with the sources of their spiritual well-being, livelihoods, and sense of belonging as communities.

Other pioneers include Indian economist and professor Amartya Sen, who won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1998 for his work on famine, human development theory, welfare economics, and political liberalism; and philosopher Martha Nussbaum, who worked with Sen to develop the “Capability Approach” to welfare economics, which centers on the importance of human dignity as a foundation for living (and economics).

There have been many more inspirational campaigners in recent times too, from social scientist Riane Eisler, author of The Real Wealth of Nations: Creating a Caring Economics (2007); economist Kate Raworth and her Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist (which has overlaps, but is slightly different from, the concept of circular economies); and Christian Felber’s Economy for the Common Good (ECG), a social movement he founded in 2010 that advocates an alternative economic model that’s beneficial to people, the planet, and future generations.

Then there are recent books like 2019’s Toward a Life-Centered Economy: From the Rule of Money to the Rewards Stewardship, in which authors John Lodenkamper, Paul Alexander, and Pete Baston outline a manifesto of economic synergism and talk of giving all stakeholders a place at the table—workers and management, shareholders and customers, suppliers and community, and, most importantly, earth's ecosystems.

All of these inspirational people and ideas have kept the flame burning in different ways for a Life-Centered Economy. But in recent years a bigger and more global sense of momentum has been felt, arguably due to a combination of the increasingly visible effects of climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic—itself a product of neoliberalism, in that it was caused by environmental exploitation and was exacerbated by globalization.

This crippling double-whammy felt, for many of us, like the straw that broke the proverbial camel’s back, and has given the movement a new sense of urgency. The time for serious change is now—or never.

Waking up to The___Dream

The House of Beautiful Business has been committed to promoting the Life-Centered Economy, more or less since our inception. Our mission to “make business more beautiful” has drawn on much of the foundational thinking of ecological economies, nature co-design, regenerative business models and sustainability, improved work environments, decentralization, diversity, and the embracing of spirituality.

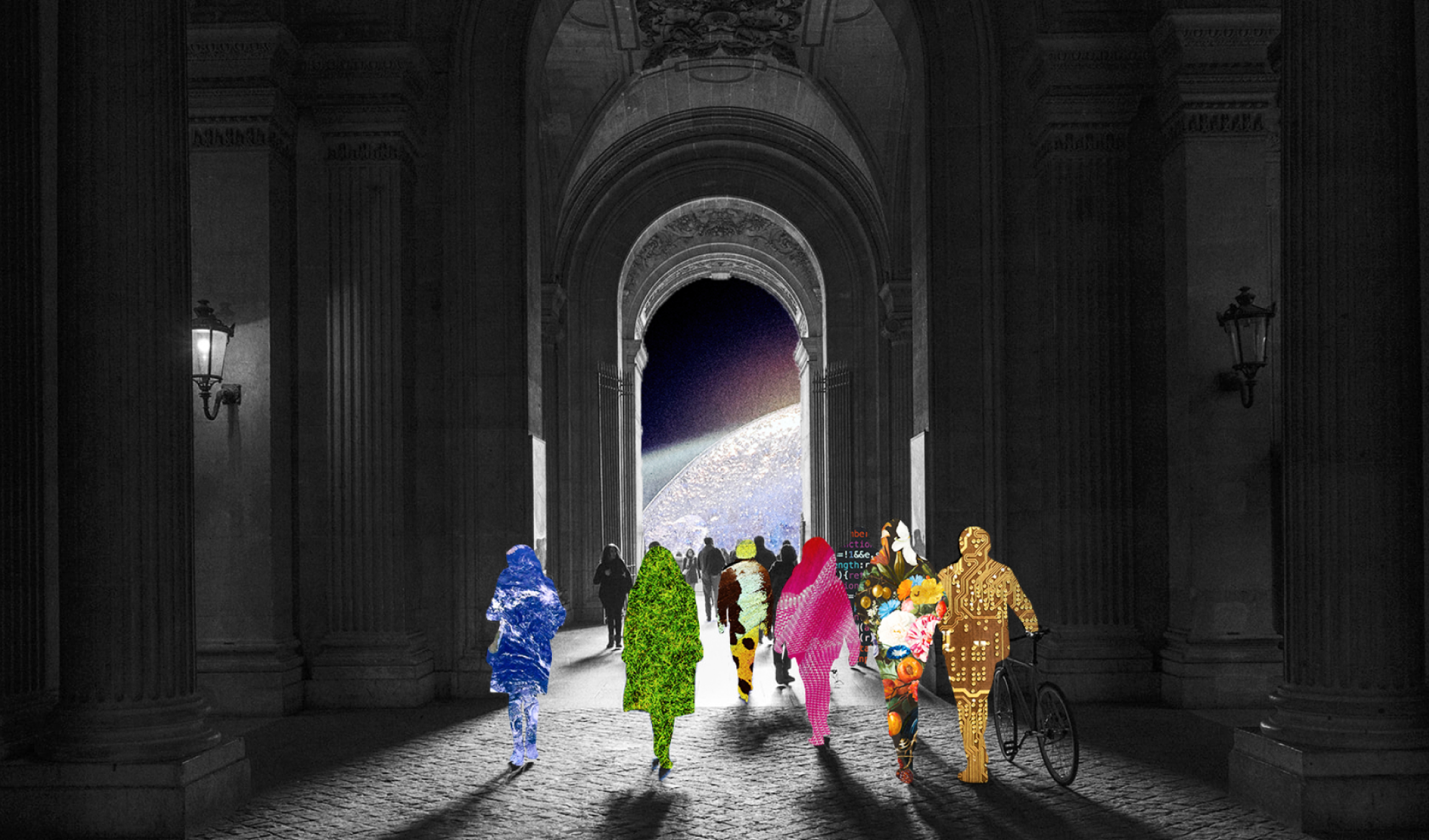

While we didn’t plant the seed, we have been doing our best to nurture it by diligently growing our community of like-minded individuals and companies, aiming to show that the Life-Centered Economy is not just an idea or a trend, but a powerful movement with real revolutionary potential. Our collective aim is a regenerative economy that mirrors and works with nature rather than exploiting it. A return to the natural, physical, and spiritual that kicks homo economicus and his obsession with maximization and mathematics out in favor of the circular, the sensuous, and the concept of sufficiency.

The biggest manifestation of our commitment to the Life-Centered Economy is coming up this summer. At The___Dream, our festival taking place in Sintra, Portugal, on June 2–5, we will be bringing together 600 thinkers, doers, and leaders who share this same vision: an awakening from our current ecological nightmare.

There is an African philosophy known as Ubuntu, a Nguni Bantu term meaning “humanity” that is often translated as “I am because we are”, or “I am because you are.” It loosely means a belief in a universal bond of sharing that connects all humanity and nature. At The__Dream, we will be celebrating the Life-Centered Economy precisely through a spirit of togetherness with each other and the planet.

Together we will learn about Bayo Akomolafe’s Emergence Network, which tackles matters ranging from the nature of science, racism, tricksters, climate chaos, and unschooling, as well as the “unbusiness-like nature of business”; and explore the concept of bio-leadership with Andres Roberts, who promotes a new style of leadership defined not by growth, winner-takes-all competition, consumption, and separation but by cycles, connection, regeneration, reciprocity, and love.

We will find out about decentralized finance (DeFi) and regenerative finance (ReFi) movements with John Elisson, through which mission-driven communities empowered by blockchain technology address climate change and biodiversity loss, and help create systems that restore and maintain the physical resources essential for human well-being.

In the realm of consciousness, neuroscience, the metaverse, and AI, we will hear from David Chalmers about what he calls the "hard problem of consciousness," and his concepts of “naturalistic dualism”, “philosophical zombies,” and “Reality+,” as well as from neuroscientist Hannah Critchlow and her groundbreaking research into collective intelligence.

Diving deeper into spirituality and psychedelics, Shani Lehrer, a multidimensional entrepreneur and ritual master, and “corporate mystic” Julie Fedele will talk about how ancient wisdoms and modern technologies can work together to unleash human potential. And Amanda Efthimiou, a mental health advocate, will discuss her work on personal and collective growth, and the wonders of plant-based medicine.

And yes, there will be mushrooms! Colin Averill, whose work centers around soil and fungal ecologies, with a specialty in what are known as mycorrhizal fungi—that is, fungi that form a mutually beneficial symbiosis with the roots of most plants on earth. Averill regards himself as a climate activist in addition to his work as a scientist, to which end he has created a start-up, Funga, to help scale his research and make it even more effective.

Also exploring the power of fungi is Maurizio Montalti, whose passion for microbiology has led to products as diverse as chairs, tables, and slippers made from combining mycelium with agricultural waste like flax and wheat. Massimo Portincaso will showcase the related potential of generative farming.

The goal is to gather all of these inspiring and impactful ideas (and many, many more) for the Life-Centered Economy and synthesize them into an irresistible experience that will move leaders to return to their organizations and lives—and change everything. Research has shown that we can be wide awake and still dream.

—Paul Sullivan