Wanted: Degrowth. Needed: Growth.

Did you feel the heat last week?

It was the hottest week ever recorded on our planet. This week, a deadly heat wave is sweeping across the south of Europe, closing down major tourist sites, prompting red alerts for dozens of cities in Italy, and sparking wildfires and evacuations in La Palma.

Meanwhile, it’s business as usual for the fossil fuel companies as they quietly backtrack from their climate pledges.

Although many of us are pushing hard and fast to decarbonize, not everyone is aware of the paradox at the heart of the energy transition: namely, that decarbonization requires us to continue exploiting our poor, exhausted planet.

Olivia Lazard is passionate and clear-sighted about the challenges ahead. She offers an articulate and well-researched perspective that outlines the obstacles, difficulties, and tensions we need to overcome. A fellow at Carnegie Europe, a non-profit in Brussels that works on European foreign and security policy analysis, she speaks bluntly about the precarious situation we face.

“Seven out of eight ‘safe and just’ planetary boundaries have been crossed,” she says. “But we are still digging into the earth’s crust to achieve not just an energy transition but a parallel digital transition. And we’re still thinking and operating according to a limitless growth paradigm.”

And that’s not the whole story. Olivia’s work for various NGOs, the UN, the EU, and donor states around the globe has given her insights into another aspect of the energy transition that isn’t so well known: the rising competition for mineral resources and the global conflicts that this creates—the current situation in Ukraine being a case in point.

Her research raises profound and urgent questions for us all. Is there a way out of the transition paradox? Do we really have to plunder the planet to save it? Can we create trade agreements to mitigate the probability of global conflicts? Her powerful 2022 TED Talk addressed some of these significant issues, as did her recent show-stopping conversation at The___Dream with TED global curator Bruno Giussani.

We talked to Olivia again to delve deeper into degrowth and alternative economies, and what businesses and leaders can do to help push the transition in the right direction…

Interview conducted by Paul Sullivan

—What is the environmental and economic prognosis for the near future, from your perspective?

We are about to hit the 1.5 Celsius tipping point. We need to be clear-headed about what that means. It is now baked in. Science doesn’t know what happens beyond 1.5, but we know it will not just be about more floods or droughts—it’ll be more shocks to the economic system that will rein in our economies whether or not we like it. As the degrowthers say, we can either do this by design or by shock. Shock means recession, but degrowth does not; it means transforming the economy.

“We are also coming into an era of more and more scarcity, in particular water. We expect that by 2030, our freshwater resources will be 40 percent less than they are today.”

Everything relies on water—everything. Not just agriculture, but every technology-oriented industry, whether they are conscious of it, or not. Last year, Taiwan almost stopped manufacturing semiconductors because of a massive drought; they were lucky because it rained. They’ve used the last year to put contingency planning into place that uses desalination, but desalination plants are also energy intensive and not a long-term solution.

—You mention degrowth, a movement that seems less vague and more solidified of late. Could it provide at least part of the solution to the current crisis?

In Europe, yes, but not in other places in the world. In Europe, there are political and cultural structures in place that could help rein in demand and create a sort of slower economy, and it’s here that degrowth can be traced back to the work of Tim Jackson, Kate Raworth, and Timothée Parrique. So in Europe, there is at least a political space to talk about it but that does not exist elsewhere, including the U.S.

There is also a dilemma with degrowth. Aside from pointing out that the current model is blowing planetary boundaries out of the water and taking us towards extinction, commentators also note that even in developed countries with advanced economies, it’s not yielding the benefits we need from a social and economic perspective; things like social safety nets or security systems are becoming more precarious.

But reducing the carbon budget and lessening the intensity of trade in Europe would slow down their capacity to welcome more products from the global south where many are pro-growth precisely because they depend on trade to climb up the development ladder. For example, people in Chile are against degrowth in Europe because they say it's like changing the rules of the game midway.

Other people say, for example, that advertisement needs to stop because it pushes us towards over-consumption. But you can’t just decommission an entire sector and say thank you very much for your services, goodbye. There’s just no easy way of changing a macroeconomic logic that has been hundreds of years in the making.

“Questions remain: what specifically do we need to degrow if anything? What is the model beyond growth exactly? Who does it first, and in what kind of sequence? With what kind of safety nets? How do we reorganize sectors of the economy so that people are not marginalized in the process?”

—Much of your work revolves around the paradox that lies at the center of the energy transition. Can you briefly explain that to us?

We’re planning an energy revolution based on exploiting a planet that has already been exhausted to a point where seven out of eight ‘safe and just’ planetary boundaries (ESBs) have been crossed. So we are doubling down on energy intensity to go through the hump of this energy transition—and not just the energy transition because we're twinning it with the digital transition. We’re still thinking and operating according to a limitless growth paradigm, and this story is not being told with the right sort of analytical backdrop: What are the risks? How do we temper or mitigate them?

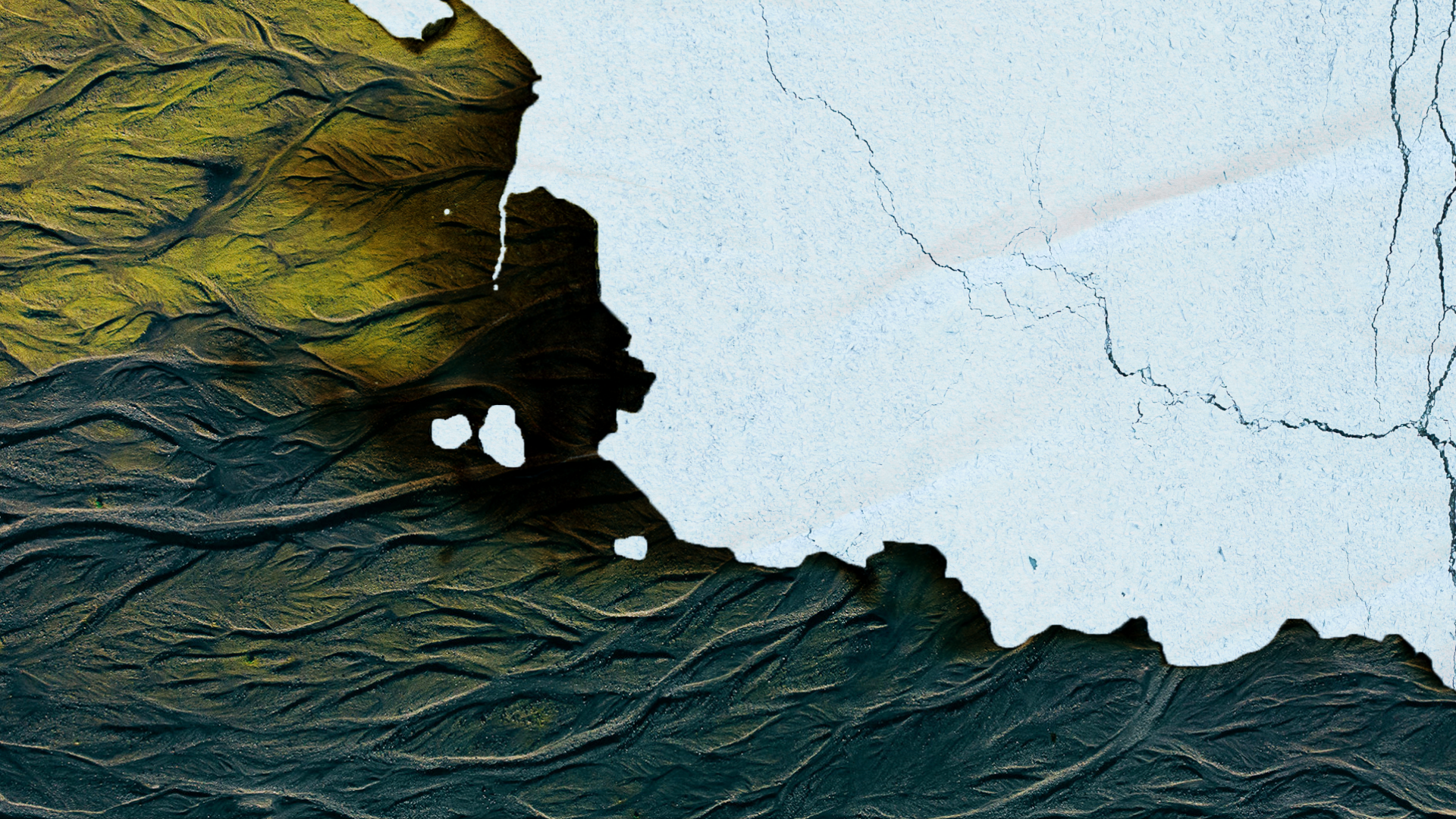

It’s not just the quantity that we need to extract, but where we need to extract from. At The___Dream I showed pictures of a Chilean mine that is 108 years old; miners there need to dig three kilometers underground to extract more quality ore, which requires more capital, more technological research, investments, and technical abilities. We're just digging deeper and deeper into the crust of the earth. But if we don’t do this, if we look for better quality deposits, then we need to go towards the Amazon, the Congo Basin, and the deep seas—places that are still somewhat pristine in terms of ecological integrity and dependencies.

But we would be going in blind, especially when we look at deep sea extraction. We may know much more about the surface of the moon or the surface of Mars compared to the deep seas, but that might still be better than exploiting the Amazon because we already know the disaster that would unfold there. In the deep seas, we have at least the benefit of the doubt. These are the completely insane choices that we have to make.

“We’re undermining the last precarious ecological interdependencies that are keeping our planet in balance and sustaining complex human civilization.”

—This obviously doesn’t sound very promising in terms of the digital revolution that we are simultaneously undergoing…

First, the idea that digitalization and virtualization mean dematerialization is a myth. It is not true at all. The expansion of infrastructure to support the digital and virtual world is extremely extensive, and we already know that the digital sector creates twice the amount of greenhouse gas emissions compared to the aviation sector. And it’s set to grow because we are still in this exponential growth paradigm story.

But it’s not just about greenhouse gas emissions; it’s also about ecological encroachment. When we look at the deep-sea cables needed to connect these continents and regions and the amount of materials needed to build semiconductors, microchips, servers, and quantum energy systems, it’s massive. We’re feeding a new beast to land us in a world of energy efficiency and the more we build those infrastructures, the more we take away from the earth as we hack away at its surface and depths. And we also arrive at the Jevons paradox, whereby the falling cost of technologies because of innovation increases rather than decreases demand.

“The feeling is that we passed the tipping point with ChatGPT. Now we have no other choice but to compete.”

We are more or less forced to innovate and be more materially intensive to have security now. But we are really not prepared or even conscious of the cost of doing so. Very few are conscious of what is happening in terms of geopolitics, information bubbles, ecological depletion, and the march towards more and more insecurity in a variety of different forms.

What’s happening in Russia and Ukraine, which is at least partly to do with the former wanting the mineral resources of the latter, is just a fault line for something much bigger and this is a story that people don’t want to hear. Human civilizations need space to process complexity and if our attentions are additionally fragmented by our phones, we simply don’t have the bio-physical ability to do this. It’s another story of us taking our humanity away from ourselves. The break is happening more from the inside, which is why we are confusing things like entertainment with pleasure, and complexity with pain. It’s really sad.

—What can businesses and leaders do to help move things in a more positive direction?

There are some analytical avenues to explore that differ between sectors. The mining sector is an important one as it is exactly at the crux of the tensions between decarbonization and regeneration. Many mining companies are looking at exploiting and extracting from places that are climate-vulnerable, water-stressed, or biologically abundant and we just cannot afford to look at extraction anymore without looking at the ecological impacts of that activity. This requires changing behaviors, which some mining companies are doing. Before, they only looked at their specific zone of operation, but now we know that any location is ecologically interdependent with others. It now involves working with biologists, hydrologists, and earth system scientists; it means sensor mapping to track the movement of seeds and water; and it means looking at our stewarding responsibilities.

In Madagascar, one company recently took two to three years to move an orchid species out of their zone of extraction. It also looked at the economic model of nature and park conservation so that their project became not just about mining but also about relocating an ecosystem and empowering humans in a poor economy by helping create a new tourism or conservation economy. This is a super-happy story for the mining sector and social impact investors, for example, could help create more of these shifting practices.

“When people say technology will carry us through, it’s partly true, but we have come to the limits of growth.”

So for business today, rather than take growth as the center of your business model, why not use risk? We don’t exactly know what that looks like anymore, but if you take on the certainty of risks and shocks, how does that change your business model? How does it change your outlook on supply chains? On economies of scale or distributive chains? On your clientele basis? Those that take this change of paradigm seriously will be more resilient and able to take us toward an economic model that’s more in line with planetary boundaries. It’s not a matter of being normative, it’s a matter of being a fast mover.

We also need more experiments like Transition Town Totnes and what Kate Raworth has been doing in Amsterdam and Brussels. What can we learn from these? What are the benefits and costs? Are they scalable? Do they encourage solidarity? When we meet someone that is pro-business and pro-growth, we should say: please give us the time and space to experiment so that we can reconcile our views that currently seem ideologically different. Because in the end, we are all looking for the same stability and security.

—Are there reasons to be optimistic about the future?

There is always a way forward. But I think the binary conversation that puts despair on one side and optimism on the other has become quite counterproductive in the conversation about climate change and ecological overshoot. When hope is a larger part of the story, people delegate responsibility away to the people who make it their business, and it stops being a collective story. Or it becomes a collective story whereby the collective is keen on ignoring reality.

“We lose time and the more time we lose, the less optimistic I can be when I speak in public. This is why many people who come and see me these days say, ‘Well, that was a bit of a bummer, wasn’t it?’ Yeah, it is! Deal with it!”

I’ve been more drawn towards stoicism because by now we have baked in so much destruction and insecurity that we have to get real about this. There is no way around grief, which is full of emotional depth, growth, and expansion. It is a beautiful process but remains a very painful one. As humans, we have trouble with the notion of pain, whether physical, mental, or emotional. But we have to get real about the fact that we have baked in a world of pain for ourselves.

How we’re going to use that pain could be part of a story with a lot of growth potential. We are about to go through a series of obstacles, difficulties, and trials that are going to reshape and refine us as individuals, collectives, and in terms of human consciousness. To a certain extent, climate anxiety is a bit like fearing death because it takes away from the pleasure of living and therefore isn’t helpful. We can draw optimism, strength, hope, and resilience instead by agreeing on the diagnosis, not shying away from complexity, and being intelligent about how we deal with that complexity.

People who deal with this complexity daily, who are mostly in a minority, have been made to feel like crazed Cassandras. That’s how I’ve been feeling for a long time. There’s nothing healthy about this, but the craziness doesn’t come from the people who are trying to tell the truth. It comes from the myopia that exists within society.