Work Is Not a Family, But We're All Parents at Work

You can listen to the audio version, featuring special guests, here.

Flash back to 2004, and this is what I recall of parents in the office: new mothers returning to their jobs after three months of maternity leave, stomachs flatter than the last time we’d seen them but faces fuller, eyes tired but containing pools of feeling they hadn’t shown before—and adopting a brisk demeanor and forced smiles, as if to say, well, all that bloat and bother is behind us now, let’s get back to work! Business culture of the time encouraged that—to not talk about the baby, this new life on our team’s periphery, lest we or our colleagues got too soft. I was in my 20s at the time, uninterested in becoming a parent anytime soon, but now I’m a mother of a nearly five-year-old who chatters incessantly and sleeps only reluctantly, and I can only marvel at the mixture of sadness, relief, and bitter exhaustion these women who wiped their hands of their maternity at the office must have felt. (Baby pictures on office desks were even discouraged; to do otherwise was a sign one wasn’t a sufficiently serious business-lady.)

Wherever did we get the idea that denial was productive? Why are figures like Alexis Ohanian, Reddit founder and investor—not to mention husband to a high-achieving woman and a man who aspires “to be known for making this world better—much better”—getting so much attention just by talking about paternity leave?

Moms. Dads. We love them. We resent them. We blame them, in life and in our careers. But we can’t deny that they make our world—one messy meal, one hug, one exasperated outburst over childish antics at a time. And they don’t necessarily have to be biological parents to do so, especially in the workplace. This week we’re exploring parenting, from a form of UBI for parents (and the potential business impact) to mentors or “work parents” to the dystopian scientific projections that suggest we might miss parents once they’re gone.

—Megan Hustad

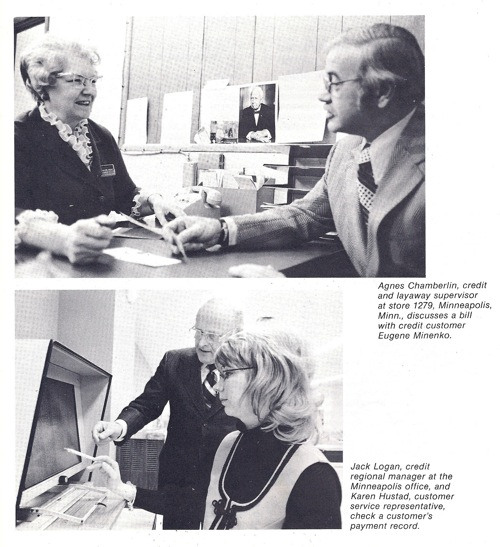

Karen Hustad, Megan's mother, working at JC Penney store 1279 in Minneapolis.

Questions for you

- Are you a good parent (even if you are not a parent)?

- Did you or do you want to have children?

- Who are your children?

- Do you spend enough time with them?

- Why not?

- At this very moment, if she is still alive, what do you think your mother is doing?

- And your father?

- What have your parents taught you about parenting?

- Is there someone else, besides your children, you feel like a parent toward?

- Is there someone else besides your actual parents who is like a parent to you?

- Is work like a family for you?

- Was your heart ever broken at work?

- Would one of your colleagues risk their life to save yours?

- Do you feel responsible for the growth of your organization?

- Are your colleagues better parents because of you?

Should work be “like a family”?

Unless you work for the mafia, maybe the answer should be no. The phrase “it’s like a family here” presumes that we want a workplace that resembles the atmosphere of our homes—and is often associated with companies where employees are expected to work much more than 40 hours per week.

But there’s a good side to the sense of familial connectedness at work. Research has shown that employees experience greater wellbeing when they have friends at work, and organizations report a sense of camaraderie as a key ingredient in fostering team dynamics based on productivity and loyalty. In a post-pandemic world where remote work remains a substantial part of employees’ lives, the need for a sense of togetherness has only increased: According to research recently published in American Psychologist, loneliness in the workplace has “strong negative relationships to employees’ affective commitment, affiliative behaviors, and performance,” and that an absence of nonverbal cues is “likely to increase employees’ concerns about being interpersonally rejected, contributing to loneliness.”

But achieving connectivity at a distance is easier said than done.

What makes a family a family are its relationships: inextricably intertwined truths, each with its own histories and stories of pride, success, and joy, as well as of trauma, loss, and despair. Family, in essence, lives within you (which were the wise words of Simba’s father in Disney’s The Lion King). You can never entirely remove yourself from them, nor they from you. Everyone contributes to an unspoken “family code” of rituals, traditions, and patterns that must not be broken. There may be certain repressed experiences and memories that cannot be discussed under any circumstances, as well as delicate topics that were never part of “dinner table talk.” And there were the characteristics and behaviors that creeped up through generations, exploding in moments of anger and resentment.

Despite the fact that every family comes with its challenges and quirks, and even though we’ve all wanted to be part of a different family at one point or another, we love our families, in the rawest form. We’d be willing to give and forgive (almost) anything, wouldn’t we?

And that’s where it becomes difficult at work. If we are “like a family” at our jobs, we might miss the bit of emotional detachment that is necessary for us to perform both loyally and with integrity. As our workspaces have become fluid, a heightened sense of building and nurturing relationships upon values and moral boundaries is needed.

As shown in the study quoted above, people tend to be more reluctant in calling out wrongdoing at work when the bonds with their colleagues are stronger. We don’t want to blow the whistle on people we share an intimate, familiar circle with. What seems like well-intentioned and protective behavior can quickly turn into a culture lacking professionalism and, worse than that, an increase in misconduct that never gets reported.

Work needn’t be like a family. The beauty at work is the unrelated relatedness you share with one another—or to put it differently, you are each other’s “kith and kin.” You share a belief in a larger mission, ideally, and probably spend more time together on a weekly basis than you do with anyone else in your life, yet there’s still a part of the other’s history that will forever remain “outside the scope.” You can take on different roles next to your functional ones, whether it’s parenting in a metaphorical sense (more on this below) or finding in work the steadiness that runs through other parts of your life. Similarly, we can learn how to deal with conflict instead of sinking into passive-aggressiveness—or worse, cynicism. We can learn to trust without knowing, rather than guilt-shaming. And we can give affirmation like our parents do at the end of the day.

And finally, unlike a family, we can leave on our own terms.

—Monika Jiang

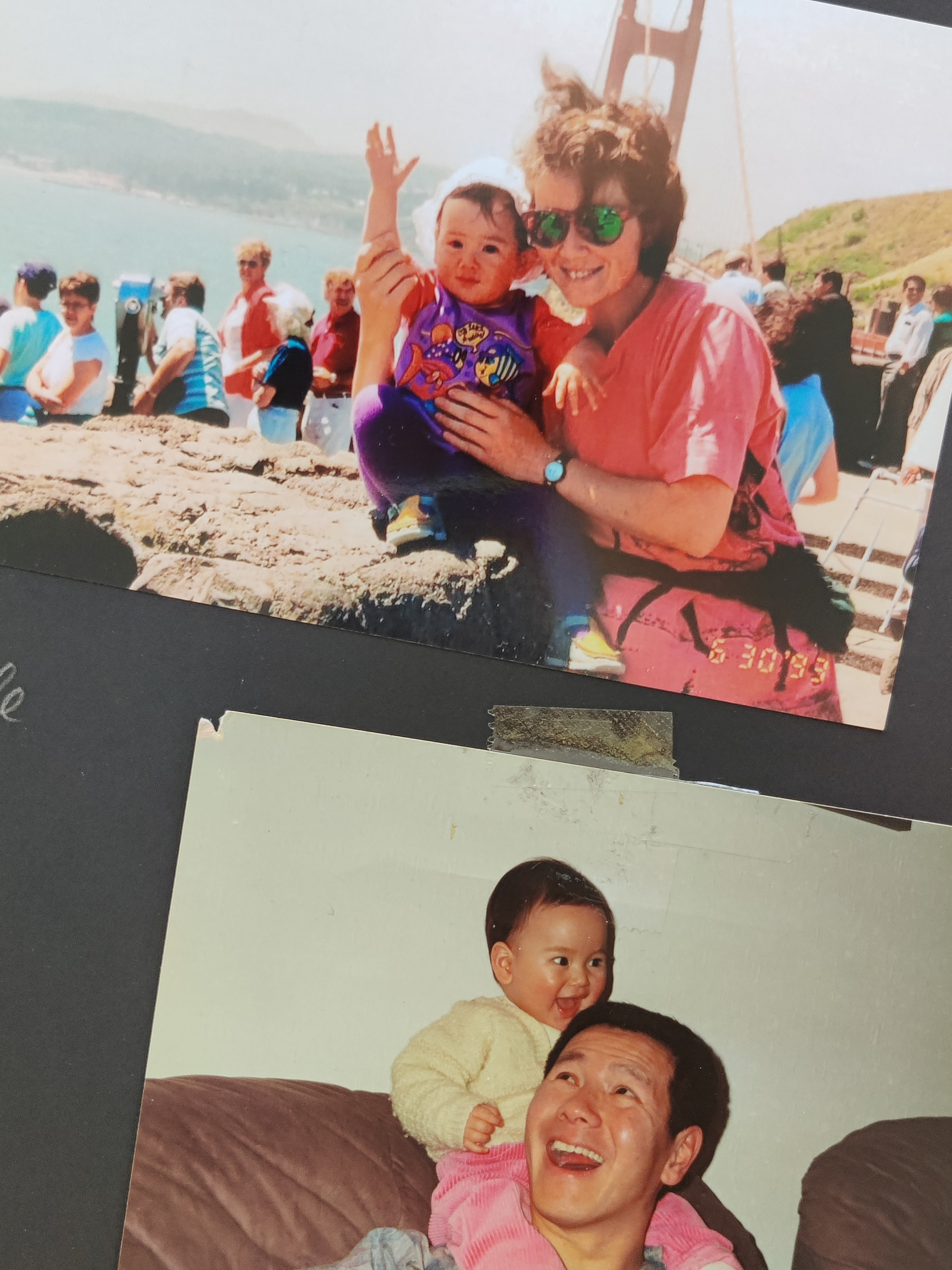

Monika with her mother, Li Jin, in San Francisco and her father, Jiang Wenzhong, at home in Grenzach

My company is my second child

An entrepreneur and mother of a seven-year-old son once told me something she admitted she would never share publicly: “My company is my second child.”

“I know this may sound frivolous if not unacceptable,” she explained, “not just because of gender expectations, but because it may seem naïve to equate actual human life with an organization. But I’m beginning to embrace this as my truth, and split my time accordingly between my two children.”

Being a founder and father myself, I can relate to this. My company is my second child, too. I have created it, and now it has assumed a life of its own, and every day it brings me great joy to simply watch it grow—and ultimately outgrow me.

And indeed, if parenting is at its roots the ongoing nurturing and enabling of growth, a founder’s relationship to their company exhibits many of the traits of a parent’s relationship to their child.

There is obviously less at stake, at first glance: no biological bond, no kinship. And yet, arguably, lives are still affected, at scale: the wellbeing of your employees, but also, depending on the impact your company’s products and services have, the prosperity and wellbeing of many, many more children.

If business is a matter of life and death, then the responsibility that comes with creating and leading a company is parental.

Wouldn’t it raise the moral consciousness of founders, CEOs, and investors if they viewed themselves not merely as the mothers and fathers of an organization, but also of society and the planet? Must they not at least try to reconcile the impossible: improving every single life in their workforce while also improving the world? And shouldn’t it be the ideal of actual parents, too, to share this global ethos, rather than prioritizing the wellbeing of only their child(ren) by all means and at all costs?

These are tough questions to answer, but one thing is clear: the business world needs better parents: people who can devote themselves to a cause greater than themselves. And people who are willing to unconditionally champion another person even if, and long after, that person has declared their independence. People who inspire and guide not just other people’s work, but their life’s work.

But in any parent-child relationship, heartbreak is inevitable.

When employees jump ship to chase their own dreams, risk their own catastrophes, become a manager, a leader, or a founder themselves, they abandon not only your child—the company you created—they abandon you. Like a child in adolescence, they will turn against and see right through you. They know how to hurt you because, if the work you did together was truly consequential, you removed your armor—you had no choice. As a parent, you realize that they’re ready to apply what you taught them and, more importantly, to apply what they taught you, but no longer for or with you. You realize they were never a part of your project, you were part of theirs.

However, unlike an actual parent, as a founder you may suffer from a second, particularly cruel heartbreak. It might just happen that you must leave your home yourself, forced out by staff, peers, or investors.

As an orphan of sorts, all you can hope for then is finding new parents or new children. But as an entrepreneur, at least you know: virtuous or vicious, the circle of life will begin again.

—Tim Leberecht

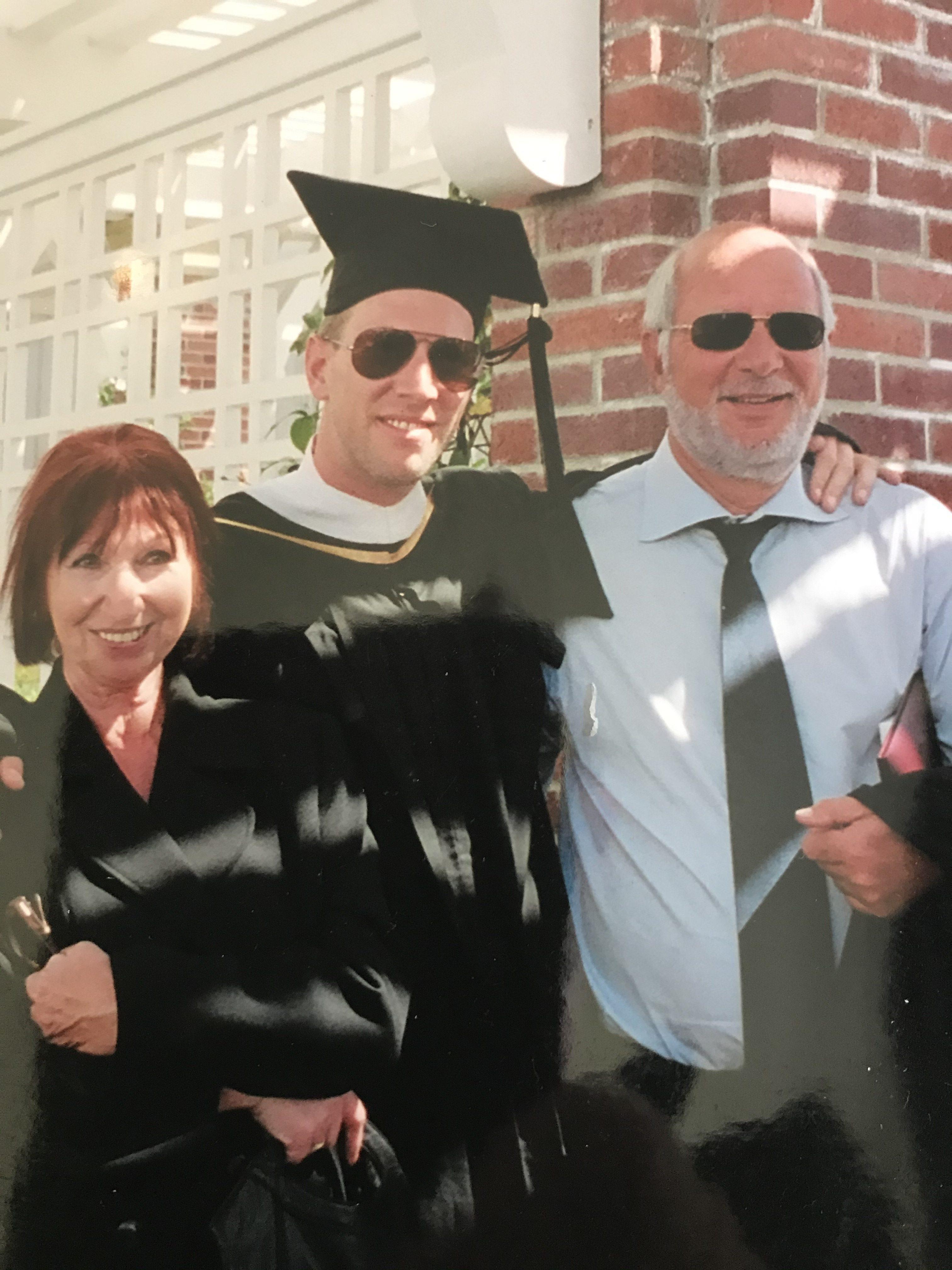

Tim with his parents, Edith and Volker Leberecht, at his graduation from USC Los Angeles in 2004

“Parents” at work

I never wanted to be a parent. With my 29th birthday just a day away, I can hear the social and biological clocks ticking: time’s running out, they whisper. You better grow up, settle into a stable relationship, and work on your reproductive duties. I’m not ready yet, and maybe never will be. And yet, I’m not here for myself. Like anyone else, I’m here for others I care for. I want to see others find and get into their thing, give them the affirmation they need, the guidance they want, the help they didn’t ask for. In other words, I do strive to become a parent in a metaphorical sense.

At work, I’m lucky to be surrounded by such parents all the time. Till and Tim are my work parents, sometimes caring and protective like mothers, always nurturing and comforting, never blaming or judging me for the way I behave or react, even if it’s deeply irrational and impulsive. And, like fathers, they find their ways of expressing trust, affection, and criticism, and display a father-like pride as their children accomplish something that means the world to them.

Megan, whom I was intimidated by for a long time (and still am, in a good way), is also a parent to me. Not only because of her New Yorker toughness, but because she’s one of the most brilliant minds I know, someone I learn from without noticing I’m learning, and whose warmth transcends Zoom screens and the comments in Google docs. Recently a few people have told me that they, too, first felt intimidated by me, which I felt quite uncomfortable with and decided, it must be because of my work ethic (thanks, Ma and Pa!).

I wonder if this sense of being intimidated (or what’s popularly called “Imposter Syndrome”) often really stems from a desire to be parented. We all want to grow as people and as leaders, and to learn and love. On this basis, my work parents give me a space to be critical, to acknowledge harsh words even though they hurt at first, and they withstand my acts of defiance. Without formalizing this into a mentorship program, but more along the lines of “mentors of the moment,” as Harvard Business Review describes it, my relationship with my work parents allows me to be the child we all are of someone, and inspires me to become a better parent someday, too.

—Monika Jiang

For (U.S.) parents who work, a light at the end of the tunnel

It’s hard to overstate the significance of the American Families Plan, announced by President Joe Biden at the end of April. Unlike almost every other developed country in the world, the U.S. has no federal policy for paid family leave, no child allowance, and next to nothing in assistance for families paying for childcare or early childhood education. If this plan passes, all that will change.

While it’s too early to say what effect Biden’s Covid-relief stimulus payments will have on the U.S. economy, studies show greater participation in the workforce among parents when childcare is subsidized.

So with the United States poised to implement a form of Universal Basic Income for parents, how will businesses change?

As the end of the pandemic seems near—at least in wealthier nations—and as the unemployment rate falls, improvements to work life, for parents and everyone else, are high in demand. For employers, benefits like childcare subsidies and time off for caregivers will be seen as essential to hiring and retention. Volvo, for example, now offers 24 weeks of paid leave for parents that they can take any time in the first three years of their children’s lives.

But offering paid leave for parents is not the end of the game. As one veteran of a tech company shared with me, some employers offer lengthy periods of paid family leave and advertise how friendly they are toward parents, but fail to replace the person taking time off with a temporary worker, or otherwise compensate colleagues who may be doing extra work for six months. This can lead to pressure on the parent to keep working during her leave, or create resentment among team members who don’t feel supported.

Mothers, especially, are having a rough time. The results from Motherly’s annual State of Motherhood survey are in, and the numbers aren’t good. A whopping 93 percent of mothers report feeling burned out. What can employers do to make this better? Not surprisingly, 64 percent of mothers said longer, paid maternity leave would make a difference, and more than half said that increased flexibility at work and support for childcare, either on-site or through subsidies, would help.

But it’s not only parents who need extra support. Flexible schedules for everyone, work-from-allowances, better sick leave, and even outplacement programs will make workers across the board feel more secure in their jobs—and make them more likely to stay.

—Eva Talmadge

Megan's son, Arlo, at her desk in New York City.

The infertile future

As birthrates fall in many parts of the world, the business of making parents has become very big business. Under the umbrella term of assisted reproductive technology (helpfully termed ART) are several procedures, associated clinics, drug regimens, and processes that involve all of the above (such as in-vitro fertilization, or IVF) that are projected to together form a $50 billion U.S. global market by 2027, according to Emergen Research.

Fueling this market are increasing incidents of reproductive problems in both men and women. In 2017 researchers released a meta-analysis of 100+ studies that showed sperm counts in Western men had halved. The reason why was deemed mysterious at the time, but additional research now points to likely culprits: hormone-altering chemicals in everyday household products like food packaging and personal care products. The book Count Down: How Our Modern World Is Altering Male and Female Reproductive Development, Threatening Sperm Counts, and Imperiling the Future of the Human Race, by authors Shanna H. Swan and Stacey Colino, offers a comprehensive look at the science behind the dire predictions of human extinction in a future where infertility is the norm, and fertility an increasingly rare (and expensive) exception.

Doctors in India, asked if they’d witnessed similar trends to those Swan and Colino describe, concurred. Kaberi Banerjee, medical director of the Delhi-based Advance Fertility and Gynaecology Centre, reported that infertility among couples in the reproductive age group had roughly doubled in his time at the clinic.

—Megan Hustad