Take a Break. Here’s How We’re Taking Ours.

For some, it is hard to take a break because leaving work would mean that work can continue just fine without us. So each of us on the House team was challenged this summer to trust that all would be OK if we disappeared for a bit—or didn’t reply to every message, which can feel like the same thing.

On my break this past July I emailed a man I hadn’t seen since I was 21, or spoken to since I was 22. He was on a break, too—selling his house in Inverness, moving his family further into Scotland’s wild. I bought more books to read, or not read. I revisited the Minneapolis art museum where I nurtured my adolescent ennui, and followed that with a mostly wordless hour at George Floyd Square—an experience I still have little to say about, other than to say it was sacred space. I bought another book about trauma and healing as a collective, community exercise, as it’s something we’re all going to have to get smarter about—in our relationships, our jobs, our business models.

In the psychic stillness of these breaks—or what passes for stillness, relative to my everyday—I made hard decisions, easier now that I’d reconnected with past selves I look back on with affection. And is that what a break is best for? To remind us of what we’ve known to be true and good all along?

—Megan

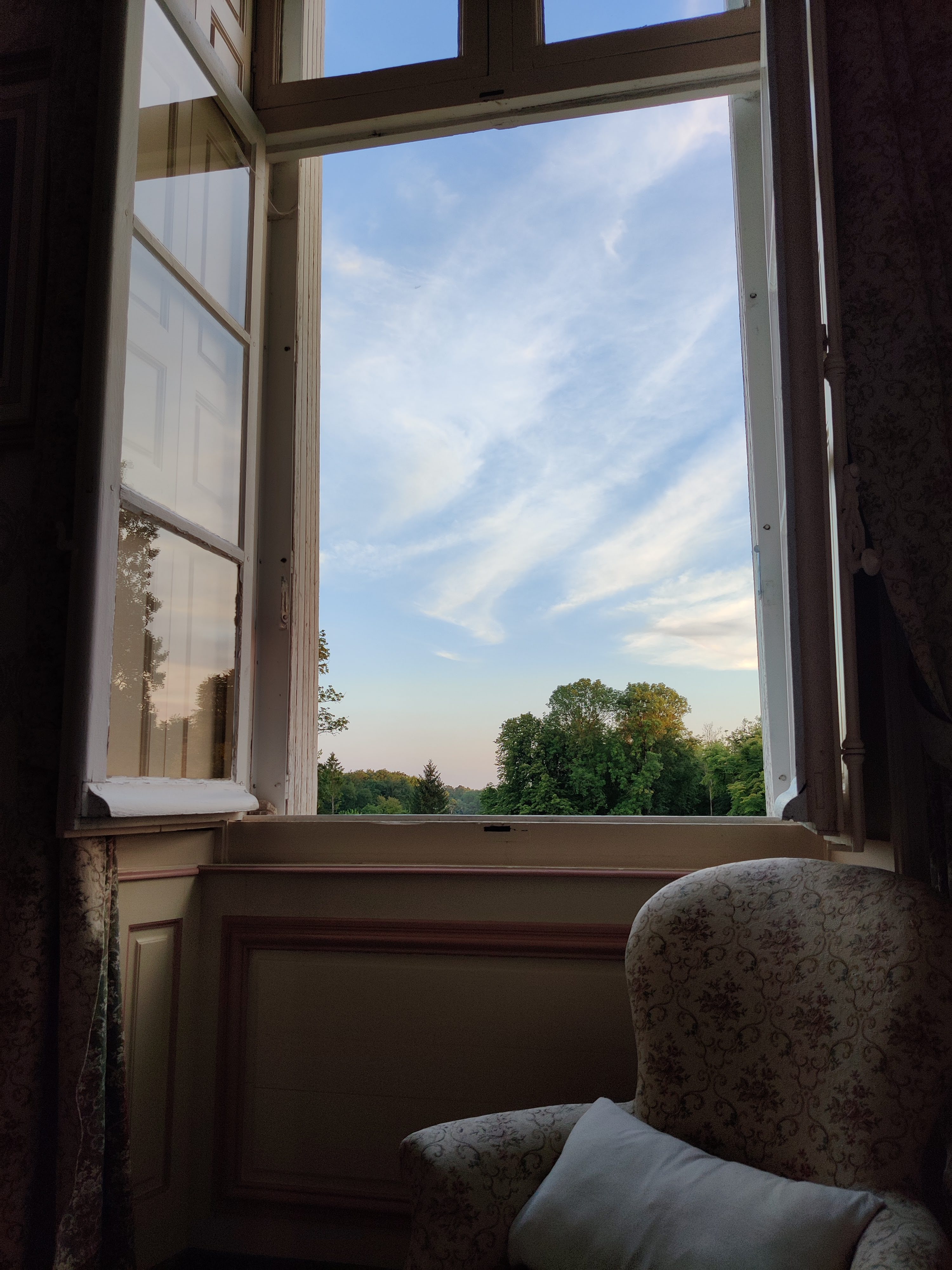

I went on a two-day road trip to a place that looked intriguing on Google Maps—first time I chose my place like this, zooming in and out, finding a spot not too far but far enough: Piney, in the Champagne region of France. On the way, my phone died just after passing Nancy. I had no map, and the villages I passed were cute but deserted on a 30+ degree Wednesday afternoon. I had sort of an idea about the direction and decided to really listen to my instinct, to French radio, which played from classics to Shouse’s “Love Tonight”—oh, and the sparse street signs. How did people travel before Google Maps? At a point where I almost gave up, one hour before sunset, a small sign appeared. “Piney!” I squeaked—alone in my car, cheering for my success.

I arrived in probably the most beautiful “chambre” I’ve ever stayed in, and fulfilled my teenage dreams of living in a Jane Austen novel. The day after I spent in the national park of Forêt d’Orient, walking off path (by accident) and encountering a group of wild boars. I read The Ministry for the Future at the lake. Swimming in the colder-than-expected water felt stimulating.

Next day, I drove back, in total about 900+ kilometers, in two days.

—Monika

The first week of August I cheated on Berlin with Paris. Not so much for the wine-drinking and the beret-wearing, but for a change of scenery, which, after months of isolation, felt justifiable. When it comes to France, no amount of friends’ tips or indie guides can save you from being the obvious outsider. It was like that for me, at least. I did try to flee the clichés, but gave in—and went the expected route: Eiffel Tour, Centre Pompidou, Shakespeare & Company. (Side note: funny how the French love naming places after people, right? There’s something to it.) Anyway, guess what book I picked up at Shakespeare? Other People’s Clothes by Calla Henkel, an “intoxicating, compulsive and blackly funny” novel about two American art students partying their way through—voilà—Berlin of the late 2000s. The reading took up a huge chunk of my weekend, which seems ironic. In that way, the break was unsuccessful.

—Dmitry

My last week off was in Greece. Between Athens, Santorini, Naxos, and Mykonos, I enjoyed the breathtaking views, warm water, hot sun, and unforgettable sunsets, surrounded by centuries of history and Hellenic wisdom.

I read a book by Cardinal José Tolentino Mendonça called The Small Path of the Big Questions while I was there. Here is a rough translation of one of my favorite essays:

There is a verse by Fernando Pessoa that brings us closer to a truth that is both obvious and hidden: We do not only measure our height, but the height of what we see. Thus, what gives us stature, what gives dimension to our life are not the more or less centimeters, but what we put in front of our eyes, what we dialogue with in an external or internal presence.

The disturbing question that arises is this: In an age that forces us to live in vertigo and with less and less time, don’t we all seem like a population of Lilliputians in the manner of Gulliver’s characters? Without availability for what is free, with no appreciation for contemplation, without giving opportunity for the amazement that opens up life or for the amazement that is life’s delight, what real height can we measure?

“Utility” has become the ruling valuation of our societies, but we also need the “useless.” Next to the bread we will always need the roses. Or rather: In key moments of our existence, if the roses are not sustaining us, not even the bread will serve us. One of the great masters of Chinese poetry, Li Po, has a short poem in which he recommends: “Sell one of your loaves and buy a lily.”

—Mafalda

My dream “take a break” is not the beach, sun, resorts, or airports. It’s more like having time and calm to actually sit at the piano, play, sight-read something old or new, open a book, and continue writing music, ideas. The rest of the year is kind of performance time. I do need that time to prepare, stretch, feed my imagination, and take a deep breath before the action starts again.

My real “take a break” is still beautiful: spending time with the kids, noisy days, screams, getting dirty on the sand, getting more sun than I wished, football, and family visits that are exhausting, but memorable and super enjoyable. I usually don’t like summer, the same as I don’t like my birthday, where I feel obligated to do certain things everybody does. But I guess I’m learning that it is a good and necessary time to take a break.

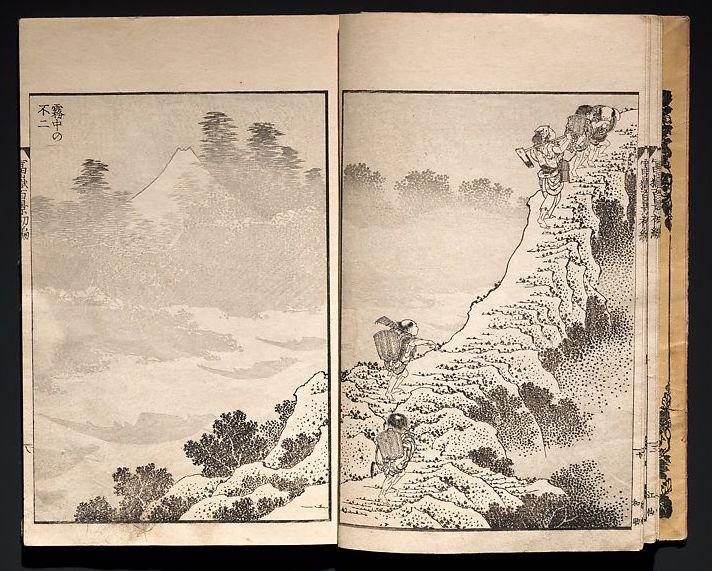

I’m having fun with a book I bought by the Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai called One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji. Just a simple book with little text and beautiful illustrations to get the imagination going.

I just bought a set of drawing pencils and a notebook and I’ll try going back to it.

—Mark

The Fagradalsfjall volcano in Iceland had been erupting since March. So on our way back to Berlin from the U.S. this summer, my family and I stopped over to see it. We knew we might not get the show we wanted, but we were as close to an active volcano as we’ll probably ever come.

It felt like a pilgrimage. We got in line behind the other lava worshippers trudging up the steep brown terrain, hoping to glimpse something molten. But the latest lava flow had already hardened into undulating alien shapes. Silently we willed the smoldering mound in the distance to give us just a tiny little spew of fire. Nothing came, but the promise and proximity were enough.

Then the treacherous part—a descent that led to the edge of where the lava flow had ended its advance. Thirty minutes of sliding and stumbling and clutching at each other, and we were there, facing brand new lava. Bits of volcanic rock lay scattered at the edge of the flow. There’s surely magic stored in these volcano-designed clumps, I thought. I put one in my pocket and we headed to dinner.

—Celeste

I flew from Washington, DC, to Portland, Oregon, where my partner and I introduced our new baby to her grandparents, five months after she was born. We stayed in my in-laws’ house and drove ourselves bananas trying to find places to work while our kids and the babysitter made noise in the next room. More family arrived: siblings and their spouses and children, and cousins’ cousins, until the house was so full that we spilled out into the yard. We closed our laptops, played on the grass and with the hose, and discovered that the secret to vacationing with children was going to bed almost as early as they did. Never had I felt so happy—or exhausted. Or so eager to plan the next trip to see everyone again.

—Eva

We drove 1400 kilometers and arrived in Brittany—a place that feels like my family’s home away from home now, as we’ve come here many times. The one constant here is wind. And with it, everything changes, all the time. The temper of the sea, the weather, the smells. It’s really refreshing. Each day I head over to a tennis court on a nearby camping ground, trying to get my boys excited about playing. I pose them challenges, and when they succeed, we head over to a little pop-up café at the village harbor and eat ice cream. Yesterday, we visited a farmer’s market (literally in the barn of one farmer) and brought home multiple bags of produce that I will now turn into my interpretation of New York Times recipes.

—Till

I’m still wrestling with Lionel Messi's breakup with Barça (my club) and reading every single commentary on the saga I can get my hands on. I’m also looking forward to Simon Kuper’s new book on Barça (to be released tomorrow, August 17).

Like Barça, I also find myself in transition, geographically, emotionally, and spiritually. I’m in the middle of moving from Berlin to Lisbon with my family; it’s a break but not relaxing. That’s OK. I will decompress in December. Until then, Concrete Love, our big gathering for the House community this fall, will keep me busy. I’m reading books by our speakers and preparing intellectually and mentally for the event (which will be like a wedding of sorts).

Once settled in Lisbon, I want to start Gaga dance lessons with House Resident Yaara Dolev (inspired by her contribution to our recent Living Room Session), just to get out of my head for a little while.

—Tim

I moved to Lisbon! It took a year of fighting. There was uncertainty amidst the pandemic, residency issues, and other personal conflicts that made me doubt I could reach what I hoped for. It was a messy middle to say the least, and not the summer break I anticipated. I was forced to a place of acceptance. There were things that I could neither predict nor control. Curiously though, I discovered in that surrender, that the moment to live in is now, and not in the anxieties of the future. That “letting go” made me feel somehow more human, and more alive in a wonderful way.

—Jess