What If We Made Things to Outlive Us?

By Greg Sherwin and Shannon Mullen O’Keefe

Remember how we have two hands?

This seems like a pretty basic question until you realize that something so obvious might become the basis for an ad campaign.

An ad campaign for what?

A right hand ring, of course.

If the left hand already has a ring on it? Diamond sellers have to work around that. They need to sell more rings as our growth economy demands.

DeBeers, the world’s leading diamond company, once spearheaded a marketing campaign aimed to persuade us that the right hand mattered too—at least when it came to wearing their diamonds. (They have not yet confirmed any investments in biotechnology that will allow us to grow a third hand.)

This campaign was pretty brilliant because it played into our human need for status. And with marriages happening later in life, shifting the focus to the right hand also meant delayed weddings wouldn’t get in the way of ring purchases (or status.) We also remember from our business school case study days that DeBeers was in the middle of making diamonds valuable in the first place.

Diamonds are just rocks, after all.

We’re a gullible species.

But the thing is, most of us don’t mind that diamonds are valuable. In fact, we like it. We desperately want them to have value. We like wearing them, and they signal status to those around us.

Status matters to us. This is not new, nor is it something we can reasonably escape. If it’s not the ring, it’s probably the car, or the gym memberships, or the NFTs. You get the picture. We like stuff that demonstrates our power to others—our standing in society. That our stuff might also signal the price of entry for belonging in a certain social group is a bonus.

With DeBeers as a case in point, however, we realize that we can manipulate what we value, whether for enjoyment or as indicators of success. So we have the power—and perhaps equally importantly: the opportunity—to rethink what it is we value.

Honestly, we might need to.

What If We Didn’t Produce and Consume for a Disposable Planet?

L.M. Sacasas reminds us in his essay, “With Want,” that in our consumer societies, ”there are inevitably two kinds of slaves: the prisoners of addiction and the prisoners of envy.” Want driven by either state “will wreck us and also the world that is our home.” In essence Sacasas suggests that when you and I satiate our desires with all the things that we consume, we’re inadvertently ruining what sustains us in the first place: our earth. An unchecked hedonic treadmill only leads to depletion and a self-sabotaging, soulless existence.

But we’re human. Many of our desires, and our desires for status, are not going anywhere. So our opportunity may be to take a page from the book of advertising professionals and reframe the kinds of things we desire.

If the ad campaign for a diamond was once “ a diamond is forever,” could we shift our desires away from disposable consumption and more towards things that might last forever?

What The Taylor Bathtub Says About How We Might Rethink Things

We know you’re probably thinking about that Fredric Jameson quote, “It’s easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism.” But we’re not proposing an end to capitalism here. We’re simply reminding ourselves that we’re in charge of our narratives for the future: how we get things done, what we create, and how we perceive value and status.

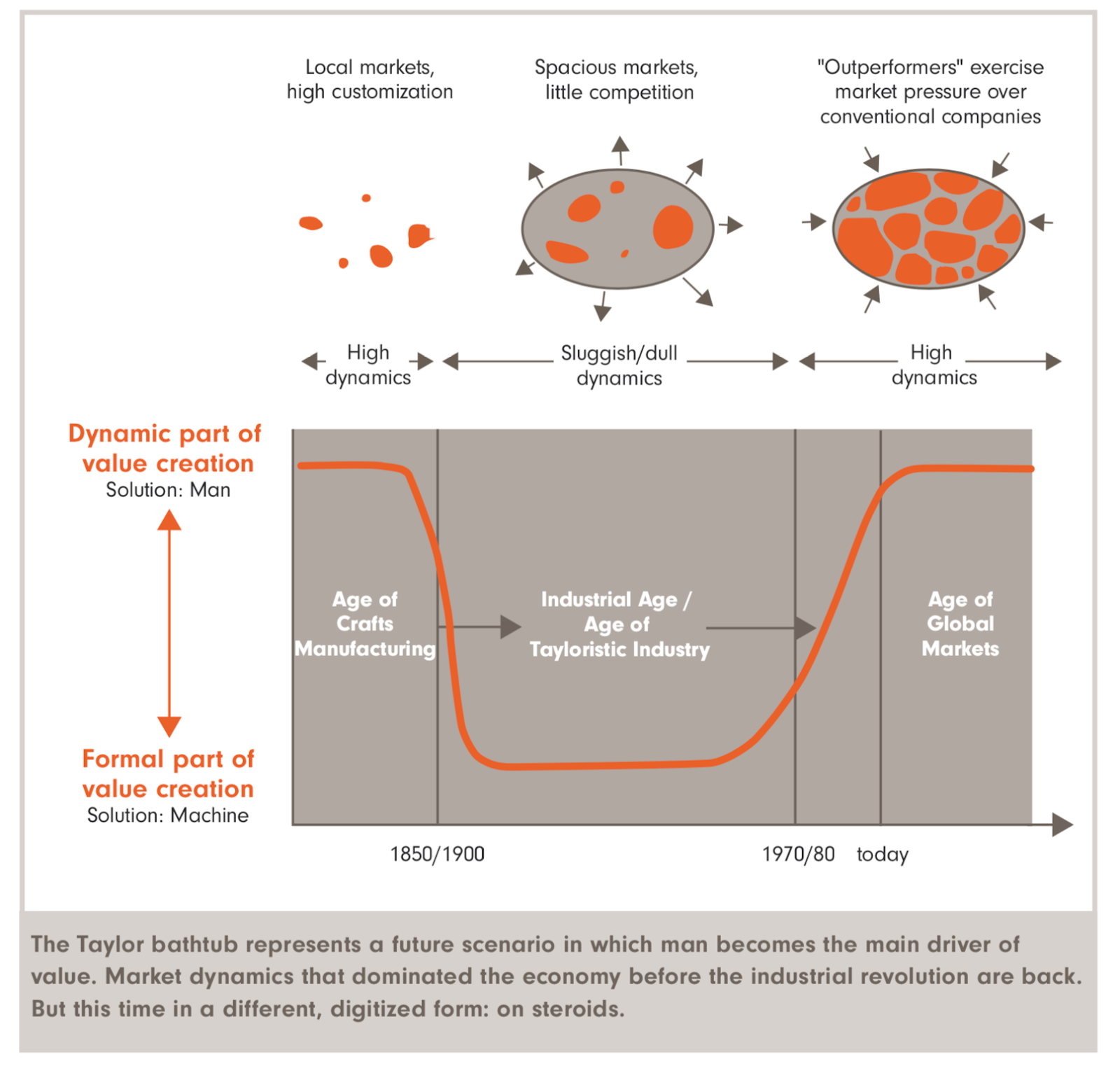

Let’s think about The Taylor Bathtub concept. (We’re not talking about the $10 million worth of diamonds in Taylor Swift’s bathtub in her “Look What You Made Me Do” video.) Niels Pflaeging introduced this concept to describe our past societal transition from artisan crafts to mass produced commodities—and how we are currently transitioning to more “mass customization.” The bottom of the “tub” represents a dominant period of one-size-fits-all industrial production; it can be viewed as a mere historical quirk bridging society between more dynamic markets.

Source: Sogeti.com

That quirk worked pretty well when we needed mass production to meet our basic needs. But we are moving on from an economy that celebrated our ability to drink the same bottle of Coca-Cola as the Queen of England, and that inspired Andy Warhol to paint endless identical images of Campbell’s Soup cans.

Today’s economy is more fixated on mass customization. Instead of staying in one of hundreds of identical chain hotel rooms, we want Airbnb stays in treehouses and geodesic domes. We want to express our highly individualized value. We seek experiences. These challenges involve complex problems that require ingenuity and ideation at the edges, not centralized command-and-control decisions followed identically by an army of worker drones.

Creating these new futures requires thinking differently.

We need to look beyond creating identical, scalable and easily replaceable things.

How Artisans Might Inspire Us

Once we meet our basic needs with cheap commodities, how might we fulfill our desires for value and status with something that will live longer than a $1,000 iPhone (which we typically toss after 2-3 years)? (Fairphone currently leads the smartphone market for longevity, but even that is only six years.) Something less fast-fashion and more like tailored, quality clothing.

Glancing over at the other edge of the bathtub, what if we turn to age-old Italian craftsmen for inspiration? Sit in a major piazza in any Italian town, and you will be struck by the craftsmanship of artisans who built something to live long past themselves.

In Italy some artisans pass down a trade over generations. You might find a “fourth generation weaver” that still produces “Umbrian textile art.” In mass production times, these craftspeople face challenges of the small business owner in a global market, as their art form is “complex and laborious.” In the tub-mindset, it is difficult for them to survive, because demand is centered around everything scalable, repeatable, efficient, cheap.

Yet if we need to undo ourselves from our disposable culture, they may also hold lessons for the future. The implicit lesson in their work might be that we have an opportunity to seek value, status, and uniqueness in more artisanal creations that stand to outlive us.

You might be thinking we’re suggesting that we throw out all our technological advances to date. We’re not. We’re not suggesting that we disavow ourselves of zippers and buttons to join Amish communities.

Rather, let’s ask ourselves this question: How might we leverage our industrial and technological efficiencies, networks, and platforms to better enable greater craftsmanship and creative flourishing at the edges?

What if we embrace a mass customization mindset and empower ourselves to produce things closer to “anachronistic works of art”? Things that we and our ancestors might keep. Things that we ourselves might only need one of in our lifetime.

How What We Value Matters

Let’s consider specifically how what we value matters to how we think about this.

Some norms of historical preservation in China, for example, demonstrate one set of values. The emphasis can be on painstaking recreation of the process rather than preserving the original atoms in a specific item. Hence it can seem like there is “nothing sacred about the original.” The value seems less focused on the item itself than on the ability to reproduce one at will.

In 2007 the Museum of Ethnology in Hamburg closed down an exhibition of Chinese terracotta warriors, when they realized the warriors were not the originals. The museum refunded money to guests and considered the works to be “forgeries” because they were essentially copies of the original. Two different cultures, two different value systems for the same items.

Contrast this with how Chinese contemporary artist and activist Ai Weiwei reveres cultural patrimony. One of his most famous works, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, used shock and awe to prompt reflection on China’s values transformation from 2,000-year-old artifacts to modern mass production.

“Marble Takeout Box” by Ai Weiwei (2015). Photo by Greg Sherwin.

His 2015 marble sculpture Marble Takeout Box confronts us with the ubiquitous styrofoam takeout box, normally made from materials that will never break down and are yet designed to be thrown away. The juxtaposition is especially poignant when we consider that China once produced the highest quality porcelain in the world. However, globalization’s advance has instead prioritized a mass-produced item of ultimate disposability and convenience, all at the expense of the health and environment of Chinese society.

What If We Value Making Things to Outlive Us Instead?

Thinking more marble and less styrofoam, what if we really latched on to that craftsman value system, that appreciation of owning and keeping something that was original.

What if we really did care about preserving the original atoms in an item? What if we valued this more than shopping for replacements, for more things.

A sealed copy of Super Mario 64, a 1996 video game, recently sold for $1.56 million. And that’s merely an original of a mass-produced item. So why shouldn’t we feel like our originals were the most precious things?

What if we were all as exacting as the Hamburg Museum director was with the Chinese terracotta warriors, dismissing replicas? Considering them to be like forgeries.

What if this value applied to our dishwasher? Or our refrigerator? Or our coat?

Would we inspire companies to build things to last?

Would artistry matter more?

Could patches and mending and repair work be cool? Might they enhance an item’s specific uniqueness and history?

The 2019 fire that nearly burned down the Notre Dame de Paris is a great example about how we can value things over time. It was not only a national tragedy in France, but threatened a symbol of human cultural heritage beloved throughout the world. Razing it for replacement with a new replica was never a desirable option.

Even though what will be built next is not a forgery, somehow, in our hearts, it will feel a little like it is. Because we cared a great deal about the original.

Imagine the potential benefits to our lives and the planet if we thought a little more like this about all of our purchases.

Creating for a 10,000-Year-Old Customer

Luxury watchmaker Patek Philippe famously values building things to last. The company embraced this with their iconic advertising campaign that proclaimed, “You actually never own a Patek Philippe. You merely look after it for the next generation.”

What if we just expanded that thinking by a few generations, and imagined building something for a “customer” that will use it for 10,000 years?

The 10,000 year clock is a great example of thinking like this. Those building it intend for it to “tick” for 10,000 years. The question implicit in the clock project is: “If the clock can keep going for ten millennia, shouldn’t we make sure our civilization does as well?” The builders of it plan that a future person will be there to hear their work chime 10,000 years in the future.

That kind of gives you shivers, doesn’t it? This type of thinking connects us in a palpable way to future human beings.

So, what if we thought of our customers in the same way?

Maybe if we build things for the 10,000-year-old customer—something Jeff Bezos is already actively working on—we think of capitalism differently. We’re still buying and selling, but we’re investing in upkeep for generations.

Our great, great, great grandkids might touch it and use it. (And the occasional vampiric billionaire.)

Creative Thinkers Love Constraints

Building for a 10,000-year-old customer is the kind of problem that the most creative thinkers love to solve, by the way.

Thinkers love constraints.

If we have to build for such a customer, we work within a constraint that asks us to really reimagine things. Business leaders with a so-called “exponential mindset” already do this by rethinking how they might achieve 10x or 100x improvement instead of just 10%.

When we do this, things like design elements change and we confront new and intriguing questions.

Questions like:

-How do we make something worth preserving?

-Will future users need to adapt to what we build, or it to them?

-How do we account for the costs of something like this?

We don’t have to look far to see that the originals of Italian crafts can get pretty pricey. However the repetitive costs of extraction, creation, distribution, and waste prominent in mass production shift to costs of ownership: maintenance, evolution, contemporizing. Given that we are arguably reaching the end of artificially cheap prices for industrial goods, as our planet can no longer absorb the externalities they impose on it, the practice of keeping things stands to grow more financially viable over continually throwing them away.

So, we have to get creative about this too.

Another question: How do we value something that might not be fully completed in our time?

Consider the Gaudi Cathedral in Spain. “Cathedral thinking” asks us to create something that our ancestors will complete for us. How might we appreciate and derive value from something in the now, even if it might not be completed until a future generation?

Questions like these inspire us to craft new futures as we create around the answers.

We know this also presents new and different challenges, too.

Do we open the door to creating things of beauty because we expect them to last? Does our craftsmanship become a lasting point of pride for us? Do we consider our work a gift to future generations? How do we ensure that those living with less can still meet their basic needs?

What will we do with all of the time we used to spend consuming?

Does this open the door to us thinking differently about work, too? Perhaps we might invest more in humans as artisans, restorers, or modernizers who care for our works as they age across generations.

Our Next Chapter

We should be clear that we’re not presuming socialist idealism here. We’re not getting rid of property, abolishing it, or subsuming it by the state.

Rather, we’re suggesting we consider a new kind of property and a new customer.

We’re suggesting that we begin to embrace scarcity as a constraint and then get creative with it.

We’re inviting business thinkers to stop thinking in terms of quarters and to start thinking in terms of centuries.

What if this invites us to imagine a narrative that helps us grasp something bigger than ourselves? A new model to rethink, reimagine, and reinvest in quality. The lasting kind. The kind that can be passed down for generations.

The diamond is “forever” kind.

And to endorse a system of consuming that asks us to again really cherish things. Not only the things, but the human beings who will use the things together with us over time.

When we do this, we might even get the added bonus of our fragile planet thriving that much longer for us, and future generations, to enjoy, too.