Carbon Coin, Inflation, and Why Economics Need Diversity

If you’ve tried to book a plane ticket, hotel room, or rental car in the past few months, you know that prices have gone up—in some cases by as much as 30 percent. But this year’s surge in consumer prices in Western countries now appears to be transitory—a reaction to shortages in microchips and clogged supply chains in the face of a sudden, post-vaccine increase in demand. The cost of lumber has come down, as has the average price of a used car. Changes in our economic system, on the other hand, may be much longer lasting. Here’s a look at some of the biggest transformations that lie ahead.

In this issue:

- Carbon Coin

- Diversity

- Modern Monetary Theory

- Fintech

- UBI

- Crypto

First and foremost, carbon: No booming economy in the 21st century is going to last if we continue to dump carbon in the atmosphere at our present suicidal pace. Enter Carbon Coin, a concept from a paper by civil engineer Delton Chen popularized by legendary science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson in his 2020 bestseller The Ministry for the Future. In the novel, Carbon Coins are issued through a central bank to anyone who can sequester carbon. Oil companies, farmers—anyone who commits to leaving carbon-producing assets in the ground, or capturing carbon in the air, receives them. Like Bitcoin, Carbon Coins can then be bought and sold on currency exchanges, with the added caveat that central banks across the world agree to buy them on a schedule, steadily increasing their price.

Mitigating or containing the climate crisis requires levels of global coordination and commitment that humanity has heretofore not seen. Perhaps economic motivation—cash for carbon—is what we need to make it happen.

Black economists might prevent the next recession

Picture this: growing up alongside your mother’s hair salon in the Bronx, a woman-dominant space, infused with the ability to show up present as yourself, where everyone spoke Bambara and embraced their full identity and wholeness, and where one of the currencies was a “susu,” a pool of funds that members of the community brought together to give to one person for that month.

This is how Fanta Traore, co-founder of the Sadie Collective (and also a speaker at Concrete Love in Lisbon), first developed her relationship with entrepreneurship, business, and economics. She was raised by a father she describes as “the first economist I’ve ever met, because he’s really great at stretching money and doing a lot with a dollar. With a family of six in New York and a wage much less than anyone should ever be living on, he was able to do a lot with that.”

Fanta grew up witnessing economic hardship and the lack of representation and diversity that lead to the groupthink and systemic failure of the 2008 recession, an episode that would have benefitted from a more diverse set of policy makers and economists from Black communities. Having worked at the Federal Reserve, which was put in place to alleviate financial crises like this, Fanta found herself the only Black research assistant in the international finance division. That lack of diversity reinforced her drive:

“Having advised the Biden transition team on what could be done around this issue, I’m hopeful about what’s possible. But there’s a lot that needs to happen. With having encouraged more Black women to go into economics, my team and I have found it’s not enough. Yes, we can diversify the pipeline, but institutions need to change. We can’t just have these stellar, amazing women go into business and be defeated by systemic racism and how it manifests in the workplace. With the Sadie Collective, we evolved to grow and meet this challenge. We’re not just about helping Black women survive in economics, but to thrive in it.”

How will economic policy benefit from more diverse perspectives? One example comes from a recent paper by David Wilcox and David Reifenschneider, both formerly staffers at the Federal Reserve, who argue that continued higher prices might catapult the post-pandemic economy toward a level playing field: “To the extent that people drawn into the labor market when it is tightest come from marginalized groups,” inflation “could also help reduce racial and other inequities” by keeping people in jobs longer and allowing them to get more experience and training.

According to Fanta, apart from monetary policy by the Federal Reserve, fiscal policy driven by the government is one of the overlooked opportunities to impact people’s experience of the economy. One example is the student debt crisis, as explained in an article by the Wall Street Journal, highlighting “how building wealth for Black Americans has been impeded by the rising costs of school despite increasing levels of education.”

The present moment presents an opportunity to spend more to encourage more consumer engagement in healthier ways, improving everyone’s individual agency.

“Student debt forgiveness, as the Department of Education has established for 300,000 disabled persons recently, can have a substantial effect on consumer participation. Reducing debt for women for the astronomically rising costs of education over the past few decades (of which Black women have the most debt) can have a profound impact on spending power for individuals. Once that’s addressed, there needs to be a fundamental look at for-profit colleges and their predatory nature, as well as other practices that disproportionately negatively impact Black and marginalized communities, like payday loans, which Colorado leads in improved policy on.”

Does that mean that inflation is good for us?

Stephanie Kelton, economist and former adviser to U.S. presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, disagrees. When it comes to government spending, she argues that asking how we’re going to pay for it is the wrong question. Instead, we should be asking: “How will we resource it?”

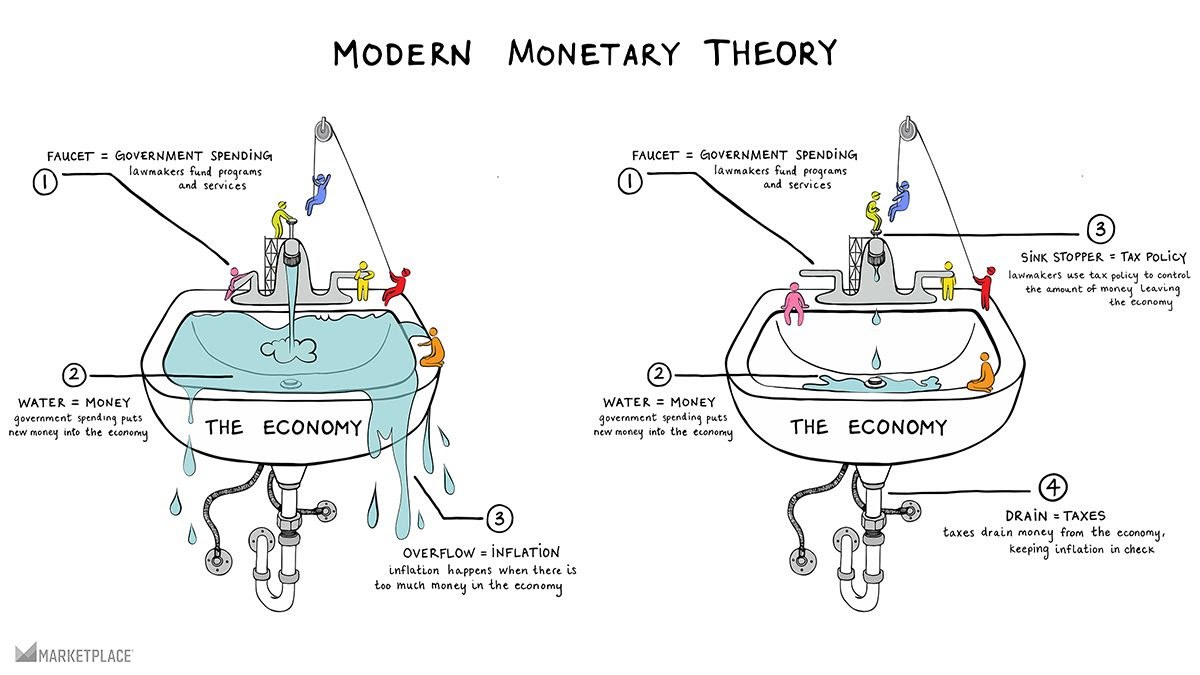

Kelton is a proponent (if not the most prominent figurehead) of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), which posits that instead of raising taxes, governments should simply issue new currency—that is, print more money—to fund socially desirable big-spending projects such as the Green New Deal. This controversial theory holds that there is no financial constraint on government spending as long as a country is a sovereign issuer of currency. “When the government spends more than it taxes,” Kelton contends, “it makes a financial contribution to some other part of the economy.” Essentially, if the government has a deficit, the private sector has a surplus. MMT has been around for a while but recently garnered more attention in light of increased government spending due to COVID-19. In fact, some observers have commented that the governments of Canada and the United States may already be practicing MMT.

How do you feel about MMT? Too simplistic, or simply brilliant? Turning more countries into hyper-inflated Venezuela, or making the economy produce more value for all of us? “Basically Keynesianism with some social-media-influencer branding,” or a truly new and effective framework?

Illustration by Rose Conlon

DeFi is poised to remake the financial system as we know it

Decentralized finance—DeFi—is growing fast: In the past year, the value of assets used as collateral in DeFi applications rose from U.S. $2 billion to $50 billion. Private investors have backed 72 DeFi companies in 2021 alone.

Loosely defined as cryptocurrency projects that use automated software programs based on blockchain to do the work of traditional banks and exchanges, DeFi encompasses not only Bitcoin but insurance, savings accounts, and derivatives trading—leaving the middlemen out of the equation. One of the main arguments in favor of this system is that these markets are more transparent than the conventional financial system because you can see every transaction on the blockchains—though this transparency is not always so clear. DeFi is also much more risky than traditional investing: Anything from problems in the coding to wild fluctuations in the value of cryptocurrencies can spell the end of your investment.

Regulators, meanwhile, are scrambling to catch up. Unlike banks, where regulators monitor the activity flowing through them, the peer-to-peer nature of DeFi leaves no bank or exchange to regulate. Which may make the programs themselves illegal, according to the CFTC. The threat (and promise) of regulation in the wake of ballooning growth has been all but constant in tech for years—but so far, at least in the United States, lawmakers have yet to accomplish much.

Fintech on the rise

For a safer investment bet, try Africa: The fintech industry is one of the most-funded categories among tech startups on the continent and is growing rapidly. Which is no surprise: Access to traditional financial services in much of Africa is lacking. A report by the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development last month delineates the nature of fintech’s rapid growth phase in Africa, and finds, not surprisingly, that half of all successfully scaling companies are based in Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa. The importance of this technology in Africa cannot be understated: Where informal workers lack the means to demonstrate that they are creditworthy, and where families without a bank account cannot manage their cash flow and savings, mobile-based fintech solutions fill a crucial void.

Meanwhile, Vietnam’s e-wallet startup MoMo (Mobile Money), launched in 2013, is struggling to maintain its lead in the mobile payments market. “The market may eventually consolidate into two or three players,” Takahiro Suzuki, managing partner at Genesia Ventures and a longtime investor in Indonesia and Vietnam, recently told the Financial Times. “But the investors behind them have very deep pockets. As long as the money keeps flowing in, many companies can coexist. It is a painful battle.”

UBI is everywhere

When we talked about universal basic income last year at The Great Wave, it felt like something that was still far in the future, after every single job had been taken over by a robot, and humans, deemed useless, demanded a share of the robots’ income. But we were wrong. In March, as part of a sweeping pandemic relief package, U.S. president Joe Biden signed into law an expansion on the child tax credit, sending almost every American family $300 per month per child. Last month, in what has been heralded as a nationwide experiment in UBI for parents, the first checks started arriving in the mail.

But the beta phase of UBI is far from over. This October at Concrete Love we’ll hear from Sara Fenske Behat, board chair of the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco. Her organization has just received $3.46M from #StartSmall, Square and Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey’s philanthropic initiative, to expand on the city’s guaranteed income pilot, providing 130 artists, mainly from communities hardest hit by the pandemic, with $1,000 per month for six months.

Other UBI pilot programs have started (or are about to start) in the U.S. cities of Austin, Providence, Alexandria, and Hartford, and last month the State of California voted to fund a $35 million program statewide. A new trial has been confirmed in Wales as well, adding the country to a list that includes Kenya and Finland in nationwide experiments with UBI.

Infographic by Scott Santens and Julia Savin

And crypto is making it accessible to everyone

According to a press release published in Modern Ghana, a group known as the Refugee Integration Organisation has linked a cryptocurrency-based UBI program to a USSD system, meaning that users without smartphones, mobile data, or an internet connection can access their funds through simple phones or landlines. Which, for refugees and others who are desperately poor, means access to potentially lifesaving funds.

Investment in crypto, too, might become more accessible soon. Security and Exchange Commission chairman Gary Gensler recently hinted at this opportunity. A cryptocurrency ETF, as explained in the Financial Times, would allow investors to buy cryptocurrency directly from traditional investment brokerages they may already have accounts with.

15 questions

Cash, PayPal, or Bitcoin?

Inflation or deficit—which is worse?

Is the opportunity to have work the most important element of a beautiful life?

What are you invested in?

How do you feel about a shorter workweek?

What life experience has most shaped your relationship to money?

Do you own cryptocurrency?

What’s the first decision you’d make with U.S. $1,000 in basic income every month?

Did you know that in 2009 fossil fuels made up 80.3% percent of the global energy mix, and in 2019 it was 80.2 percent?

Is capitalism the problem—or (part of) the solution?

What is $2 trillion? The U.S. COVID economic stimulus bill. Seventeen Jeff Bezoses. Two Alphabets. The total of assets held by the Norwegian oil investment fund. A thousand Wembley Stadiums. The annual cost of getting to net zero emissions by 2050 (with the cost of failing to do so estimated at at least $600 trillion).

What do you consider to be alternative forms of wealth?

What have you given without expecting anything in return?