The Power in Losing Hope

“Hope” has become a powerful word as we struggle toward the end of the pandemic. The promise of medical breakthroughs, of more personal protective equipment (PPE), of vaccines, and of a more just method for their distribution, has, for many of us, kept us going. We’ve endured months of lockdowns and loneliness by clinging relentlessly to hope.

But what if hope isn’t the answer? I spoke with Bayo Akomolafe, philosopher, writer, activist, professor of psychology, and executive director of the Emergence Network, about what it means to lose hope, and what not having hope allows us to see.

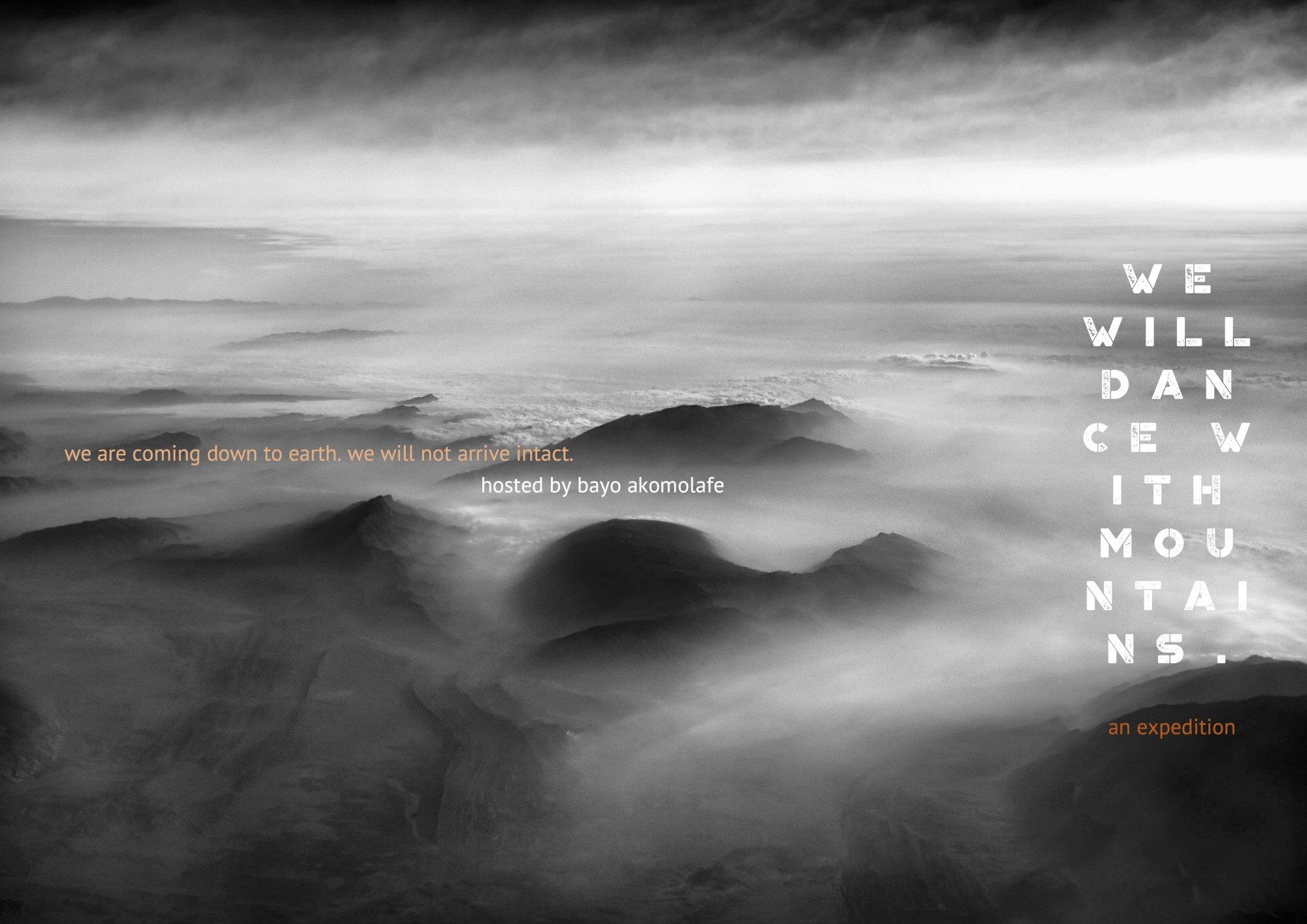

Bayo is globally recognized for his poetic, unconventional, and counterintuitive take on civic action and social change. He is the author and editor of We Will Tell Our Own Story!, with professors Molefi Kete Asante and Augustine Nwoye, and These Wilds Beyond Our Fences: Letters to My Daughter on Humanity’s Search for Home. Furthermore, he serves as special envoy of the International Alliance for Localization and hosts an online course, We Will Dance with Mountains: Writing as a Tool for Emergence. In all his work, he inspires an activism that does not treat the crises of our times as exterior to who we are, and that raises the question of whether our response to the global crisis of civilization, ecology, and colonization is part of the crisis itself.

He considers this a shared art—exploring the edges of the intelligible, dancing with posthumanist ideas, dabbling in the mysteries of quantum mechanics and the liberating sermon of an ecofeminism text, and talking with others about how to host a festival of radical silence on a street in London—and part of his inner struggle to regain a sense of rootedness to his community. In short, Bayo has given up his longing for the “end-time” and is learning to live in the “mean time”: in the middle, where we must live with confusion and make do with partial answers.

Bayo will speak at our Concrete Love event in Lisbon (and online) this fall.

When I conducted this interview with Bayo last week, he was in Chennai, India, and his wife, son, daughter, and himself were recovering from COVID-19.

— Tim Leberecht

In 2017 you published These Wilds Beyond Our Fences, in which you look at some of the world’s most pressing questions through the lens of fatherhood, specifically in letters you wrote to your then three-year-old daughter, three-year-old daughter, Alethea. What will you tell her about the pandemic?

The pandemic has shown us that we're not the lords that we think we are, that we’re not sovereign. We’re not independent. We're more intimate beyond nation-state boundaries and borders than we think we are. We call this era, this epoch, this post-Holocene period, the “anthropocene” for a reason. It’s a controversial term, but the way we use it and the way it’s been used, and where I sometimes deploy the term, is to invite us to sit with this idea that we’re not alone. In a sense, we're living on an alien planet. And it has always been alien. We thought we had everything together, but we don’t. The modern settlements that have created our bodies, created our senses of stability, are withdrawing their endorsement. And so we’ve become fugitives, we’ve become refugees, even within our own home environments.

My letters to Alethea in the book were about home, and where to go when home becomes unhomely or strange. When that happens, you need to learn to be humble. You need to learn to slow down. Speeding up and trying to fix things might get you deeper into the mess that gave birth to the crisis in the first place.

In one of your essays you write, “My ultimate purpose is to show how working faster most likely reinforces the crisis we are trying to evade.” You also use the term “coming down to earth,” which sounds like falling from grace. How do you make that resonant so that people are not scared?

I wouldn’t rule out fear altogether. It has its place. My broad response to this question is that history doesn’t support the idea that the more we put in work, or think faster, and work harder, the more things shift, especially for people who look like me and come from the part of the world that I come from. It has been the case historically, even contemporarily, that the more we have been recipients of Western benevolence, the more the world has tried to fix our problems, the more those problems have been exacerbated. So we have a ringside view of the irony of agency.

Contemporary forms of activism are increasingly part of the architecture of the norm. So that even with our most radical acts of escapism and emancipation, it seems we are entrenching ourselves deeper and deeper into the paradigm that gave birth to them in the first place. There’s a carceral toxicity at work here, a cyclicity, if you will. We keep on going round in circles, driven and motivated by the premise that human beings have this essential power, and that we’re cut off from the rest of the planet, and that it's left to us to fix things. I’m so glad that conversations that are sometimes caught up within the field of discourse that is new materialism, posthumanism, indigenous insights, are beginning to disabuse us of the idea that we can unilaterally change our world.

I think the world is agentially alive. It’s vital. And it makes vital, stunning, shocking contributions to how it comes to matter. This is not about us winning the trophy at the end of the day. This is probably about us learning to listen, learning to slow down. Because if we keep on doing the solutions—not that solutions are ruled out, I’m not trying to create a binary here—but most of the solutions that we come up with are still entrenched in the paradigm of mastery, of colonial mastery. And that gives birth to so many problems.

The last time we spoke, you asked me about the predominant metaphor or structure that still underlies all of our thinking. You said it’s the slave ship. Can you elaborate on the significance of the slave ship?

I feel drawn to think of the slave ship as an energetic, vibrant, simmering figure that hasn’t disappeared. It hasn’t been composted. It’s still functionally, practically alive in how the world comes to work today. And by “the world” I mean modern civilization. Industrialization did not just spring out of thin air. It was built on the backs of slaves, it was built on the backs of the Middle Passage, it was built on the backs of the transatlantic slave trade, it was built on the backs of cotton plantations. It was built on the back of excavation, denial, displacement, all of that, and the slave ship was key to that.

The story we tell is that the last slave ship, possibly called Clotilda, just fell to the earth, became waste and was forgotten. I think that that’s not exactly the case. I think the shoreline ate up the slave ship and became the slave ship. So that the ways we work today still mimic the hierarchical structures, the architecture, the presumptions, the power dynamics, the inequities that were available and functional within the slave ship.

That brings me to notice that we might still be in the slave ship: the colonization, the colonial settings, that we’re in. The idea of justice as inclusivity seems to me as a way of bringing people from the lower deck, which was where black bodies were incarcerated, to the upper deck. And I like to say, maybe “justice” doesn’t serve the radical aspirations, the desirous imaginations, we might be invited to attend to today. Maybe we need something more radical than just climbing up on deck while we’re still within the same slave ship.

Something more radical—what might that be?

I don’t know, brother. And that’s it. If I could come up with a manifesto—I’m very, very shy about notions of the future, of utopian ideas of arrival. That is not to say that I’m not already engaged in anticipatory dynamics and futural politics. But I feel that part of our deep-threaded, loamy composting, place-based work today is to stay with the trouble.

There’s something about this moment that almost invites us to not be so eloquent. To pause. And not be so trigger-happy with our visions of the future. That there’s some kind of work that invites us to slow down, to stay with the confusion. And that is not something on the other side of thinking about what the world might look like. But there is some kind of work that maybe invites us to work with the tensions of this time.

By tensions, I mean, for instance, the phenomenon of grief, of grieving and grief. There’s something about staying with that, that might allow us to have new kinds of visions, because visions are not human phenomena. Visions are territorial assemblages. So unless we meet the world and form new wild coalitions of acting, we will continue to reproduce visions that keep us in colonial, toxic cycles of becoming.

Tell me about the course that you teach, “We Will Dance with Mountains.”

“We Will Dance with Mountains” is conceived as, in many senses, returning to the slave ship. Conceptually speaking, there’s some aesthetic there about staying with the trouble, and where else is there trouble except acknowledging that we are still behind bars, if you will? Spiritually, theologically, politically, socially, we are creatures of these times, of our contexts. So let’s own it, and stay with it.

The course is basically about carving out a space for radical conversations. Beyond just radical conversations, and beyond the move of safety, it’s about inviting people to descend into places of depth, and what the Greeks would call katabasis, to have conversations that may not even be permissible on the surface. So we’re exploring cancel culture, we’re exploring identity politics and racial dynamics. And the invitation here is that maybe there’s another way of thinking about it, that might constitute another place of power. So all of these happen within the conceptual framework of staying within the trouble of where we are, and withdrawing from thinking that we are beyond it, or that we can summarily create a future with our own hands.

Some of the concepts you examine very critically, specifically the idea of human agency, of a human-centric, anthropocentric view of the world, seem integral to the world of business. In many ways, business is instrumental in driving change. But you could also argue that real change is not going to come from business. What do you think?

I don’t know that real change isn’t going to come from business. I don’t even know what business is, in these indeterminate times. Here’s a sweet and swift confession. When the course grew to the size that it was, it meant more income. And suddenly, we’re in a different tax bracket, and the government, looking in, needed to classify me, and my wife running the course, and the team around us, as a business. This is the first time that I, as an academic, and a psychologist, and a recovering one for that, had ever been close to the idea of business. I’ve never seen myself as a business person, or as even interested in the notion of business. But right now, the thing that I’m doing is seen in some quarters as business.

I wonder if the very notion of business is already changing. I wonder what a pandemic brings to the picture that we may not be able to see or language at the moment. I think as value changes, and the way we think about value, and the way we think about the human body, and the way we think about human settlements, and the way we even conceive about work in the way we conceive work, and language, and becoming, and travel—as all of these change, I think business will have to change as well. And business might be unrecognizable. The business in 10 years might be unrecognizable to us today. So I wouldn’t rule out business as already being radicalized by a pandemic, or by the chaos of the moment. I think it just might well be. And so maybe the questions that we need to look forward to might come from the realms and the places that you are curating, brother.

How optimistic are you about the behavior change, the mindset change, that’s needed to tackle climate change?

Pessimism is my weapon. That might be scandalous to some of us who need to champion hope, or who need to be optimistic. I’m not ruling out optimism. I’m not even thinking about pessimism as the other in a binary or dualism, that situates optimism against pessimism.

Let me put it this way: black bodies can no longer depend on the idea that the world is working in our favor. For all of us, for that matter. Remember, I’m still sticking with this idea that we’re on the slave ship. To those who insist that we hope, I wonder what hope does within the shackled environment of the slave ship. The slave ship needs to crack open for me to even begin to understand what the world might do with us, what generosity might mean, what hospitality might look like. So I don’t have a lot of optimism with these gatherings. I wouldn’t rule out visiting them, I wouldn’t even say don't go there or don't gather. But I’m looking for something that is a shock to thought. Something that disturbs continuity, something that breaks us and stops us in our tracks, and invites us to go to places that we've never gone before.

COP26, for example, seems like just another event in a long tradition that started in the 1970s, and that will probably continue for a century. We’ll continue to gather and debate and hopefully put by the feet of nation-states this burden to change. I’m not confident that the present assemblage of nation-states can address something that is so incalculable like climate change. We're still trying, for instance, to solve climate change. I am of the opinion that we are climate change, that you can’t solve the planet, that the planet is climate change. And we’re in a time when our bodies are being demanded to do something different that modernity cannot even allow us to see. We’re still seeking sustainability and permanence in a time when we’re being invited to die well, to let go of our permanence, to let go of our categories.

For me, I think there is some generosity, or some generativity, in losing hope. Losing hope is not a place of despair or abject poverty. I’m talking about the kind of losing hope that allows us to see and glimpse other places of power, like the favela in Brazil. I think the favela is a wonderful experiment in losing hope in the city, that the city will not provide. This is not true for everyone that inhabits the favela. But the very idea of the favela, its historicity, its performance, seems to me or strikes me as a repudiation of the city’s continuity. We may not have buying power, we may not be able to walk into a shopping mall and buy goods like you. But we will find a way of making scrap and waste into things we can use. Moreover, the world that sustains the shopping mall is not going to last for so long. So you had better be in the favela.

What do you like so much about Charles Eisenstein’s work, who will also be speaking at our Concrete Love event in October?

Charles and I became fast friends and brothers because of the way we feed each other. Not just because of the things we say. It’s because we don’t know, and we don’t pretend to know. We find in ourselves spiritual allies, willing and eager to explore the realm of not-knowing as a place that is alive with multiple knowings and doings. I sense the poetry in Charles too, in his work. I think poetry is the language of survival in a time of crisis.

When things get messy and muddy, and uncertain and indeterminate, you call the poet, you don't call the scientist, or you call the poet, who could be a businessman-poet, who knows, could be a scientist-poet, who knows—the world is hyphenated in strange ways.

The relationship I have with Charles, his poetry, his work, is an invitation to not be so sure about the things we’ve taken for granted. And to use that uncertainty to power ourselves into different places of power.

The interview was conducted via Zoom and edited for length and clarity.

Tim Leberecht is the co-founder and co-CEO of the House of Beautiful Business.