The Three False Idols of Business: Productivity, Efficiency, Mobility

Mobility is a false god.

That is the belief of a recent movement that deploys an extreme form of immobility as a radical act of protest: the “lying flat” movement. It began as an internet meme among young generations in Southeast Asia and China and is now spreading to the U.S. and Europe. Basically, a growing number of young people have decided to simply lie flat and — do nothing. Lying flat serves as a protest against the pressure to be constantly on the move, constantly working, producing, “optimizing.” It’s a refusal to go to work, to advance their careers or even have one.

It’s a silent and emblematic expression of a desire for something else. And while not all of us are lying down — maybe we would like to but don’t dare — I believe that many of us are feeling a similar disenchantment with the three idols of business-as-usual that we have been worshipping for far too long: productivity, efficiency, and, yes, mobility.

Let’s start by unpacking the dark side of productivity: Only a third of workers worldwide are fully engaged at the workplace, according to a Gallup survey. A record number of people worldwide are planning to leave their employers or are considering it. A study poll found that only one activity is considered less desirable than work: being sick in bed. Depression, burn-out, and anxiety levels are at an all-time high. No wonder that a recent tweet proclaimed “I do not want to have a career,” and it racked up over 400,000 likes.

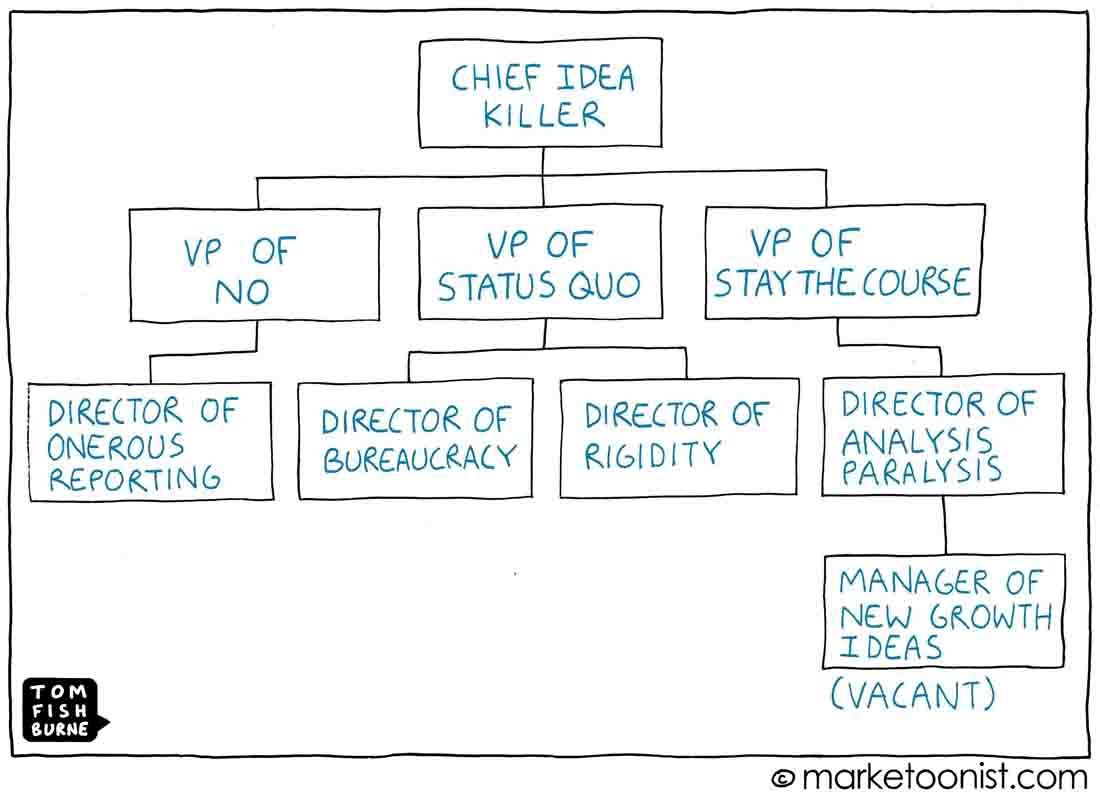

Those of us who do still want to have a career, often feel stuck in corporate structures that enable bureaucracies of fear. Despite all the talk about informal, agile structures, flat organizations, and purpose, we are still being forced into boxes and expected to be flawless, consistent productivity machines

Optimizing ourselves to death

Disenchantment with the pressures of productivity has only been aggravated by digitalization. Digital technology has done one thing really well: to optimize whatever can be optimized.

It is not only tracking our objective performance, but increasingly also our subjective performance: our emotions, our relationships. Take this app called Don’t Worry be Happy that scans your facial expressions, and if you stop smiling, if you stop being happy at work, it deletes all the progress you’ve made over the past hour. If you think this might be a joke, or a satire, it may well have been, but the app did exist and Microsoft’s productivity dashboard is certainly real. It collects and analyzes user data across the suite of Microsoft applications to come up with a “people experience score.” Add to that the demand for employee monitoring — or rather surveillance — software that has increased by 55% since the beginning of the pandemic, and you realize we’ve reached the furthest, most discomforting corners of the quantified self regime.

The truth is, when optimization and efficiency are the only game in town, when we’re not allowed to digress, to deviate, to create our own path, to waste time, then we won’t be creative, we won’t be innovative, we won’t be imaginative. As we are competing with ever-smarter machines, the concern is not so much that they become smarter than us. The real danger with our optimization obsession is that we humans become smart machines ourselves. The question is not: will machines be able to think, the question is: will we humans still be able to feel?

And finally, efficiency and productivity are the main two drivers behind mobility. We need mobility to increase productivity, and we want it to be efficient. But we are now commuting between different realities that are far more complex than the locations we once knew. As we strive to come closer to one another, in the real world or the digital metaverse, we realize that speed and convenience are not everything. Mobility as a means to get around and get ahead has become questionable, at least for those of us for whom transportation is a luxury.

The question now is: which trips are really worth taking?

Winning: a losing proposition

There is a common thread among the false idols of efficiency, productivity, and mobility: it is the idea, on the societal level, of progress; on the organizational level, of constant growth; and on the personal level, of getting ahead. It is the idea that there are winners and losers, that we are playing a finite game that is winnable.

But what if it’s not winnable? What if winning is the problem? What if winning at all costs inevitably leads to the ultimate loss: the robbery of our planetary resources and our own health?

“Working faster most likely reinforces the crisis we are trying to evade,” the Nigerian philosopher Bayo Akomolafe says.

To resolve the existential crisis of our times, we must challenge the productivity-efficiency-mobility regime and embark on a different kind of trip, to those innovations that take place inside us. There is a direct link between regenerative economics and regenerative work, between planetary boundaries and our own personal boundaries, between the ecology of our planet and the ecology of our selves. This link is the very catalyst of the shift from business-as-usual to business that is beautiful.

Beautiful business: this may sound like romantic bluster or a luxury, but it is not. It is imperative. As we struggle through the climate crisis, the public health crisis, the mental health crisis, we need business to be beautiful more than ever.

But how? How do you make business beautiful?

I’d like to present three design principles that might help. They are small steps but powerful.

Do the unnecessary

Most of our customer- and workplace experiences are designed for convenience. Seamless and effortless. Soon, everything our heart desires will be delivered to our doorstep via drone. In Japan, even a Buddhist priest can now be found on Amazon, just a few mouse clicks away. It’s called obosan-bin, or priest delivery.

But why do people hike the Alps to catch a few seconds of the leading bikers flying by during the Tour de France? Why, in cities worldwide, do people gather to swim in the ice-cold ocean — a phenomenon called “ice-swimming”? Why do some people walk on hot coals? Why do more than 50,000 people embark on an annual pilgrimage to the Black Rock desert in Nevada to celebrate the Burning Man festival, a week-long communal experience of radical self-expression, self-reliance, and letting go of one’s conventional identity, sleeping in the desert sand?

This quote by Lila Davachi captures it perfectly:

“We say we want more time, but what we really mean is we want to create more memories.”

And we are all in the business of creating memories, and making meaning.

Let me illustrate this with another story about leadership.

I once worked at a company that was the result of a merger of an IT outsourcing firm and a small design firm. We were bringing together 9,000 software engineers with 1,000 creative types. To unify these two very different cultures, we created a new third brand. The brand color was going to be orange. As we reviewed the launch plan, we decided to cut the purchase of more than 10,000 orange balloons we had planned to distribute to all staff worldwide. Thousands of balloons just seemed cute and unnecessary. But I now know that our decision marked the beginning of the end. That these two different companies would never become one. And sure enough, the merger eventually failed.

Was it because there were no orange balloons? Of course not. But the “cut the orange balloons” mentality permeated everything. And when you cut the unnecessary, you cut everything. Leading with beauty means rising above what is merely necessary. So, do not pop your orange balloons!

Steve Jobs knew all about the power of the unnecessary. For seven years I worked at Frog Design, the design firm credited with inventing the minimalist Snow White design language on Apple’s early products. Our founder, the industrial designer Hartmut Esslinger, who had worked very closely with Steve Jobs, once told me that Jobs was even involved in the meticulous interior design of Mac’s motherboards. He quoted Jobs as saying: “People don’t see it, but they feel it if something looks good on the inside.” Jobs alluded to the soul, the spirit of a product.

Alfred Kaercher, the founder of the German cleaning products company Kaercher, had this to say: “Our customers are not staying with us because of what we do, but because of who we are.”

He alluded to the soul, the spirit of a company, to a culture shaped by relationships to customers and employees that are not based on transactions, but on something far more profound and sustainable: intimacy.

Create intimacy

Recently I came across a study that stated that the average person in the U.S. has only one close friend. This is not just an American phenomenon. The numbers are similar in other parts of the Western world, and they have been deteriorating over the past few years, so much so that sociologists speak of an age of social isolation, a loneliness epidemic.

It is astonishing though, isn’t it, given the fact that we’ve never been more connected, never been more communicative, than at this point in history? We check our smartphones up to a 100 times per day. People go to the restroom at parties so they can check their emails.

And yet we are lonelier than before. Why?

“The opposite of loneliness is not togetherness, not connectedness — it’s intimacy,”

the writer Richard Bach explained, and we are in dire need of more intimacy in these digital times. In fact, the desire for intimacy is so strong that some obscure business models are already catering to it. For example, this new trend coming from L.A.: for $30 you can hire a stranger to walk with you for 30 minutes. It’s called “people-walking.”

What does this mean for the workplace? Studies show that how employees feel about their company’s culture depends mostly on their relationship with their coworkers. And what are relationships other than a string of small moments? There are hundreds of them in our organizations every day, and they have the potential to distinguish a productive life from a beautiful one. Small moments of attachment create intimacy.

Artists can teach us a lot about designing for intimacy at work.

During the height of last year’s lockdown in Germany, the Stuttgart state theater launched a series called “1:1 Concerts.” The idea: host 1:1 concerts between one musician and one listener at a time; 10-minute long encounters that started with a silent gaze at each other’s eyes for a minute before the musician then performed a composition they thought was the best suited for the moment. The series quickly became popular. 1:1 concerts took place across Stuttgart, including in the airport terminal. The series was featured in the New York Times and expanded to various cities around the world. People across all age groups, cultures, and backgrounds enjoyed time that was “thick” instead of being lean and efficient.

The notion of “thick time” is entering the modern workplace: it’s about quality time and creating deep connections. Mindfulness initiatives are similarly becoming increasingly popular. SAP, the software company, has appointed a head of mindfulness and runs a global mindfulness training program that is constantly oversubscribed. Daimler, the carmaker, in some departments, has begun to kick-off each meeting with a minute of silence.

And there are more experimental formats, such as silent dinners. I took part in one a few months ago, hosted by a business magazine in Berlin. I’ve experienced a number of awkward moments in my career, but spending 90 minutes in silence with a group of 20 German business executives was certainly one of the strangest experiences I’ve ever had. It was the first dinner where I liked every single guest. The CEOs at the table didn’t say a word, but they were there, fully present.

Intimacy also applies to the cusilestomer relationship.

Arvin, my favorite barber in the world, who runs his own shop in San Francisco’s Noe Valley neighborhood, told me a touching story when I last saw him. One of his customers approached him during lockdown with an unusual request: to perform a virtual hair cut on him and his family over Zoom. So Arvin organized some mannequins which he used for the haircut on one side of Zoom, while his customer and his family sat on the other, chatting with Arvin. The whole procedure lasted a few hours. It was a beautiful performance for everyone involved. And this really stuck with me: As people are looking for ritual and companionship in days of self-isolation, a barber’s job is changing, too. Arvin also told me that he had to teach another, elderly client how to groom himself for the first time. The barber as coach, experience designer — and friend.

Or consider Buurtzorg, a Dutch caregiving organization. A few years ago, the company made a radical change: it removed all hierarchy, all titles, and all official roles, and instead formed small teams of nurses, fully empowered to make autonomous decisions and do what they considered to be in the best interest of their patients. Two things happened: First, Buurtzorg has grown into a highly successful business. Second, the cost per patient decreased, which suggests the organization became more effective.

Despite all the time savings of automation, let’s not forget that the most powerful thing we humans can experience is another human being who genuinely cares. In B2C or B2B industries, we are longing for modern-day versions of the old-fashioned concierge who acknowledges us as unique individuals, offering up an escape from algorithms and filtered preferences.

We don’t want personalized experiences; we want personal experiences.

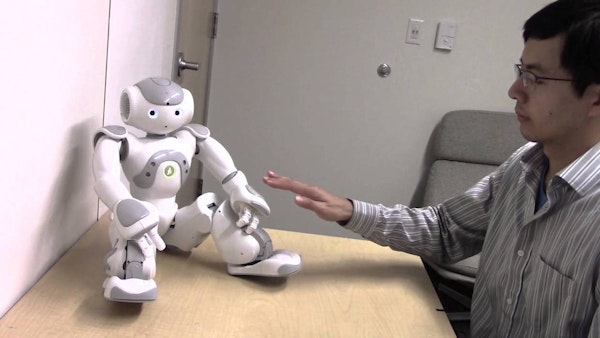

Intimacy at the workplace or in the customer relationship is an intimacy between human and human. But how about intimacy with machines? Is it possible? Researchers have studied this topic for a while, and they have found that we indeed form emotional attachment to machines. Chatbots can become our best friend (the majority of millennials already indicate they would prefer a chatbot over a human customer service agent).

Take this new study from Sweden: people confronted by a tiny humanoid robot called Nao, who begs not to be switched off, found it difficult to turn the robot off, even when they were done working with it. We are quite willing to feel something for machines, which is also why robots are increasingly used in mental health and elderly care (take this example of Paro, an empathy robot used in Japan, a culture in which objects and nature, and not just humans, are assumed to have a soul, to have spirit).

There’s one thing though that machines will never be able to do and that is inherently human and inherently romantic: to lose. Machines always play to win, and losing is not an option in their super-optimized world. But for us humans losing is an existential condition. We have no choice but to let go, and yet, we need to learn it, again and again.

Let go

Let’s start with the people who know a lot about winning and losing: the sports fan, and specifically, the football fan. Of course, the football fan wants their team to win, but what is equally important, if not more important, is how their team loses. The most painful defeats often form much stronger bonds to a club than the most glorious victories.

In business, however, we only play to win. We’re conditioned to win at all costs, and there are myriad business books and business school classes that want to teach us just that: how to win. But I’d argue that is going to change: in the future, we will all be losing, or at least losing more often. We are already losing the stability and continuity of traditional employment. We are already losing control over our brands, thanks to social media. Leaders are going to lose their authority in increasingly networked, flat, and decentralized organizations. We’re going to have to commute between different projects, cultures, and identities more frequently. We are going to have to enter and exit relationships more often. We will have to reinvent ourselves, again, again, and again.

To do so, we need emotional mobility, or, as psychologist Susan David calls it, emotional agility: the ability to embrace so-called negative emotions such as grief, sorrow, and melancholy, and to let go of attachments. Only with emotional agility will it be possible to cope with the more frequent transitions, and to become comfortable with small (and big) losses.

There’s a new breed of leaders who embody this kind of emotional mobility, these new qualities that reside in the negative space rather than the positivity of traditional leadership concepts. People like Jarcinda Ardern, the prime minister of New Zealand, who said that political leaders can be both empathetic and strong and that you don’t have to be aggressive to have an impact. Or Ada Colau, the mayor of Barcelona, who in a citizen town hall admitted she didn’t have answer to a question she was asked, that she didn’t have a solution for every single problem thrown at her, and that she had to think about it. Or Eva Karlsson, the CEO of Swedish outdoor retailer Houdini, who during the height of the pandemic last year turned to her customer, full of self-doubt, and asked them whether she should shut down all of Houdini’s marketing channels as they just seemed obscene in light of the suffering of so many people affected by COVID. She externalized her doubt and shared it openly with her customers, not afraid to seem weak or wavering. The customers’ vote was clear: they wanted the channels to stay open as they provided some much-needed distraction. But they appreciated her asking them and expressing her self-doubt. Or Emilia Roig, the executive director at the Center for Intersectional Justice in Berlin, who reminds us that our victories are pyrrhic and always someone else’s loss.

From business-as-usual to beautiful business

To do the unnecessary, to create intimacy, to let go — these are three of the qualities of beautiful businesses, and they indicate a broader cultural shift away from the smart, connected age that has dominated our lives this past decade or so, to a new era where a different set of virtues and qualities is becoming important:

- From planning to sensing

- From formal and rigid to fluid and flexible

- From happy at all times to permission to be sad

- From explicit and numbers-based to ambiguous and poetic

- From Big Data to Big Intuition

- From risk-averse to vulnerable and imaginative

- From efficient to deep

- From human-centered to life-centered

- From hard and harsh to soft and tender

- From having all the answers to asking questions

- From business-as-usual to Beautiful Business

I’m an optimist. If we do the unnecessary, create intimacy, and retain the ability to let go, to lose, if we combine these aspects of our humanity with exponential technologies, then we can not become exponentially more productive, or exponentially more efficient, then perhaps we can indeed become more beautiful, in business and beyond.

This is a slighly edited version of a keynote I gave at IAA Mobility 2021 in Munich on September 7, 2021.

If you are interested in deepening this conversation, join the House of Beautiful Business, a global platform and community for making business more beautiful.

The House will host its signature gathering, this year with the theme Concrete Love, from Friday, October 29 to Sunday, October 31, 2021, in Lisbon and online, and from November 1 to November 26, 2021, online.

Meanwhile please sign up for our newsletter!