Sexism, Burnout, and Why Afghan Women Are Strong

Nothing about the chaos that began in Kabul fifteen days ago, when Taliban forces first entered the city, has been good news for Afghanistan’s women and girls. Claims by the Taliban that their orders for women to stay home are temporary, until their fighters “are trained to respect them,” ring hollow, and are widely seen by women there as an excuse to reimpose Sharia law. (The Taliban gave similar “temporary” orders—that never expired—when they controlled the country from 1996 to 2001.) Any promises of moderation seem unlikely to be true.

What does it mean for a country when half its population is excluded from full participation? Outside of Afghanistan, women left the workforce in disproportionately large numbers last year as the COVID-19 pandemic began, and millions of them won’t be back any time soon. “Roughly five million women still can’t work due to child-care issues,” said U.S. vice president Kamala Harris in May. Today we’re exploring how everyone benefits from their participation—and why women don’t earn as much as they should.

In this issue:

- Benevolent sexism

- Unpaid labor

- Women in Afghanistan

- A conversation with Maryam Gardisi and Inge Missmahl

Most of us think of sexism as something that tells women that they’re less than: that they can’t compete in the boardroom, or in serious negotiations; that they’re not better drivers or better at spatial skills when in fact men aren’t necessarily better at those things, either. But sexism can be “benevolent” as well. Melissa Hogenboom, author of The Motherhood Complex (and contributor to our Concrete Love gathering in Lisbon this fall), explained to us what “benevolent sexism” means:

Benevolent sexism is when you suggest that women have certain vulnerabilities or personality traits that make them better carers, which sounds like a compliment, but isn’t. It’s like oh, well, women are naturally more empathetic, they’re better homemakers, or women are more caring, so more likely to take care of everyone else. It diminishes a woman’s voice at the table. And it’s just not true

Women aren’t as different from men as we like to think. Much of what appears to be biological differences are in fact learned behaviors. While there is evidence that infant boys and girls will prefer trucks or dolls, respectively, widespread beliefs about who is biologically better suited to care work are unsubstantiated. “Women become more competent or caring because they’re expected to do so literally from birth,” Hogenboom told us. This can be hugely detrimental to their income. “Research shows that some women go into careers where they know the hours will be more flexible or more amenable to family life later on.” These careers, not surprisingly, are almost always lower paid.

Care work

Then there’s the work that isn’t paid at all. Women across the globe perform unpaid care work at a rate up to ten times the number of hours put in by men, according to a report by the OECD. “The day-to-day lives of women around the world share one important characteristic: unpaid care work is seen as a female responsibility.”

What would the world look like without women’s unpaid contributions? Without the cooking, cleaning, childcare, eldercare, and care for the disabled, without the transportation, shopping, and myriad other ways that women support others without being paid? One day in Iceland in 1975—known afterward as the “long Friday”—90 percent of women in the country went on strike. “It brought the whole nation to a standstill. Men across the country scrambled to fill in, taking their children to work and overwhelming restaurants,” write Gus Wezerek and Kristen R. Ghodsee in the New York Times. According to an analysis by Oxfam, Wezerek and Ghodsee go on to explain, women’s unpaid work around the world would add up to U.S. $10.9 trillion if they were paid for it. “It exceeds the combined revenue of the 50 largest companies on last year’s Fortune Global 500 list, including Walmart, Apple and Amazon.”

The value of their work is staggering, but even a number in the trillions still falls short: It’s impossible to quantify the toll that care work takes on women who perform it. As Kate Washington writes in Already Toast: Caregiving and Burnout in America—quoted in Anne Helen Petersen’s must-read on eldercare last week in Vox—“Burnout kills empathy and makes worse caregivers of all of us who suffer from it.” In a recent report by Insider, 68 percent of women versus 55 percent of men reported feeling burned out during the pandemic. In countries where social safety nets are weak—where childcare is unaffordable and eldercare requires navigating a byzantine patchwork of services and fees—the work, and the burnout, disproportionately falls on women.

Women in Afghanistan

One of the worst places in the world to be a woman is Afghanistan, where an estimated two-thirds of girls do not attend school. That number is not likely to increase now that the Taliban has taken over the country. Denied their right to an education, women there are increasingly forced to work informally, stuck between a need to feed their families and a near-total ban on their ability to do so. So they take laundry, perform odd jobs that they can manage to do entirely within their homes, and work in the opium-production trade.

The OECD has concluded that the informal economy comprises as much as 80 percent of overall Afghan economic activity, meaning that official growth estimates are of only limited utility: A report by the United States Institute of Peace has found that half of Afghan women in female-headed households are sewing, embroidering, or washing laundry for others. As one Afghan participant put it, “economic activity is critical to the empowerment of women, especially in Afghanistan, where women are confined to the four walls of the house,” and where weak, broken, corrupt institutions make it critical to allow women to build businesses at home.

With the U.S. invasion in 2001, opium production reached new highs. Last year the pandemic pushed more women and children into the poppy-lancing process, though the exact numbers and impact of this shift do not show up in national accounts.

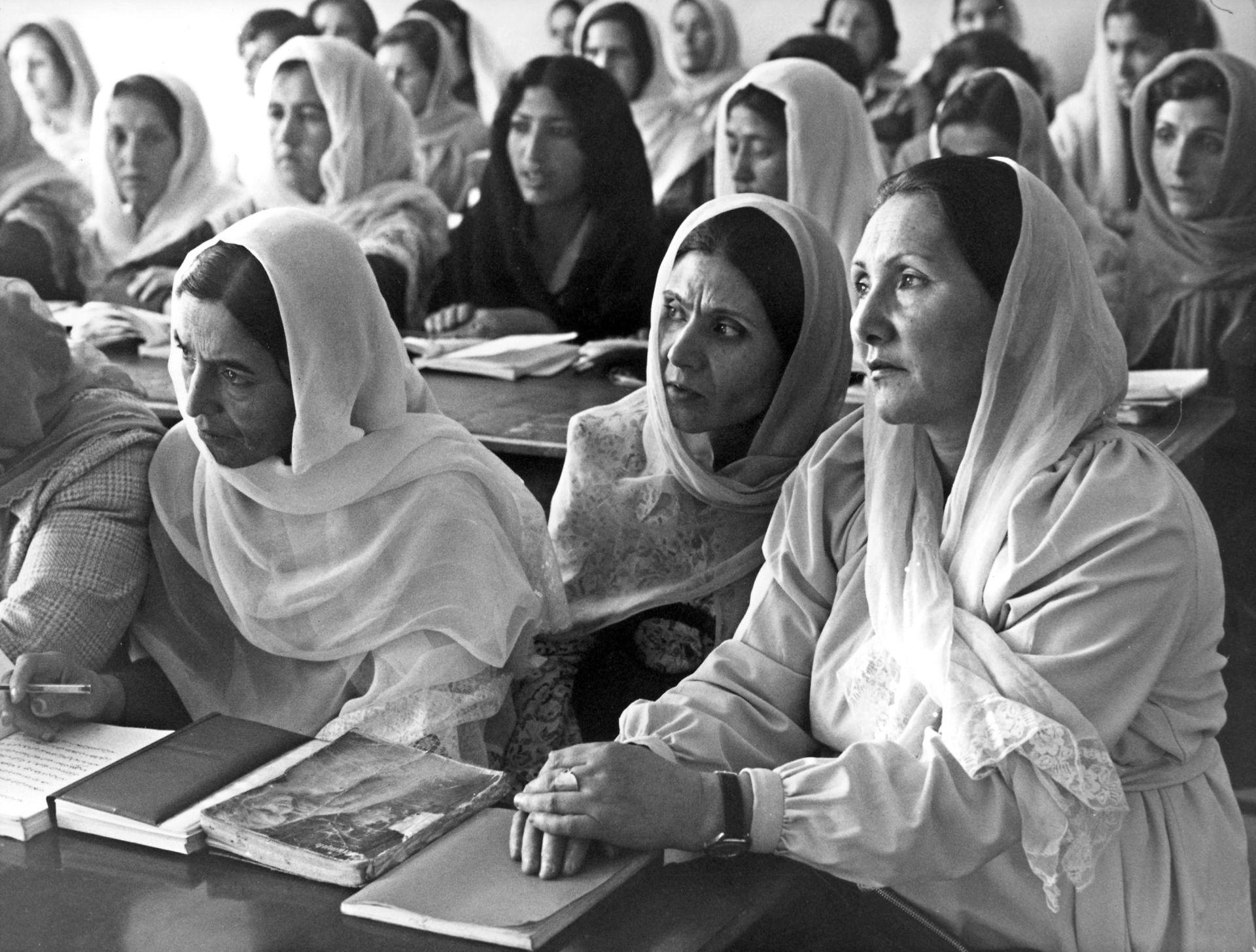

Photo by AFP: Afghan women attend a workplace literacy course in Kabul in the 1980s

|

Artwork by Shamsia Hassani: Nightmare/ كابوس Afghanistan 2021 افغانستان ١٤٠٠

A life of her own

So what are the prospects for women in Afghanistan now? We sat down with Inge Missmahl and Maryam Gardisi, managing directors of the International Psychosocial Organization (Ipso) in Germany and Afghanistan, to discuss just that.

Over the course of 17 years, Ipso has been active in the field of psychosocial care and sociocultural dialogue, promoting peace and social cohesion. Missmahl, who first began working in Afghanistan in 2004, shared her experience interacting with Afghan women in their team and counselling training:

Afghan women are thirsty for education and work. In our own organization, for example, all leading positions are managed by women, even in the more conservative provinces. What’s problematic are assumptions, particularly influenced by Western societies, about how Afghan women are or not, and how these lead to actions that are not culturally sensitive. That I had to learn myself, too. We cannot impose ourselves, but we have to truly want to understand what freedom and independence, and other values, mean.

Gardisi, who fled from Afghanistan to Germany as a teenager with her family in 1990, explained how growing up between many different realities for women shaped her sense of what was possible:

My aunts were my role models. They were doctors, lawyers, and architects—so I wanted to become like them. At the same time my mother is a Pashtuni woman, with a more traditional ethnic background and a strong religious affiliation, where motherhood and caretaking remains at the center. I loved both sides and have seen them coexist in harmony, which represents the diversity in the country.

Though there are more than 18 ethnic groups and a range of subcultures in Afghanistan, each offering varying degrees of independence and liberty, all are equally endangered by Taliban rule. Going forward, Gardisi foresees ongoing conflict:

Women now have had a taste of freedom. They will not have it taken away from them like that—we’ve seen their courage in some of the protests last week. I think they’ve gone through so much hardship to not fear as much for their own safety as we do, perhaps in Western countries. They’re strong women, they will stand up and fight for their rights.

For Missmahl, working and living in Afghanistan has taught her much about womanhood itself, and women’s role in the world:

One thing I have learned is that Afghan women are very, very strong. They are capable of adapting to new situations, and they are the ones keeping families and groups together. My deep respect goes towards their openness, curiosity, and readiness to change in a pragmatic sense, to simply get things done, because at the end of the day, there needs to be a meal on the table. And their ability to connect to each other and to other people is often very courageous. In these years I became more conscious of the role of women in our teams and in our families.

After decades of hardship and blocked opportunities that limited the free development of their lives, Afghan women are not about to give up their rights.

15 questions

Are you OK?

Do you have a maternal side?

How do you express it?

How is womanhood embodied for you?

Which woman (of the present, past, future) is your greatest inspiration?

Which story with a female protagonist do you love?

What is your favorite women-led business?

How much do you know about the women’s rights movement, historically?

How much do you know about other civil rights movements?

Have you sacrificed progress on professional goals to care for other people, or maintain other systems (household, partner’s profession, and so on)?

If you were the boss of all jobs and wages, what hourly rate would you set for childcare? Caring for elders?

Does gender equality exist in your organization? How can you tell?

Which gender stereotypes do you still believe in?

Do curtailed freedoms in one place affect lived experience in other places?

Are you aware of how free you are?