Overwritten: Trauma, Authenticity, and Love

by Tim Leberecht

2023 has been a year of trauma.

For a word that once had a rigid clinical definition, trauma has undergone a rebrand. You need only scroll through social media for a taste of the many things the term can now describe. On TraumaTok and TraumaGram, a new generation of trauma-informed youth wield therapy-speak to explain every conceivable feeling, habit, or personality trait. Whether you’re hoarding shampoo bottles, oversharing on Instagram, or feeling as though the hours of each day slip away, it can all be chalked up to a “trauma-response.” As Ana Marie Cox observes in The New Republic, America has discovered its favorite diagnosis. If you’re not traumatized, you’re not normal.

Whether you consider this assessment to be reasonably fair or think it grossly minimizes things like war, famine, and racial violence (namely, old trauma) there’s no denying that the trauma-industrial complex is soaring. More and more people identify as traumatized and seek therapy of all kinds — cognitive, dialectical, psychodynamic, even eye-movement desensitization — to improve their quality of life. Psychedelic therapy is the latest treatment to re-emerge, offering patients a guided hallucinatory experience in which they can reprocess their trauma and change the way it impacts their daily lives. Who knows what innovative method will be next.

At the core of many of these approaches is a belief in the instability of the human memory, and the theory that how we think about the things that happened might actually be more important than the things themselves. For decades now, conventional wisdom has held that our memories aren’t stable, but written anew every time they’re called to mind. Highly malleable, the memory-function in our brains is no archive locked-up by key, but a fickle storyteller who feeds on new experiences, feelings, and stimuli and loves nothing more than to curate, edit, omit, and invent. An awareness of this changeability has shifted the course of traditional psychotherapy.

Stories are never true

In The Body Keeps the Score, Bessel Van Kolk argues that trauma constitutes a special type of memory, different from memories of neutral experiences or things memorized by rote. A recent Yale study shows that the brain doesn’t even process trauma as memory; instead, trauma is stored in a separate cognitive entity with different neural pathways. Even more fascinating is that our brain doesn’t label this entity “the past,” but effectively categorizes it as a present experience, which explains why a triggered trauma can provoke such intense physiological and sensory reactions. In other words, trauma is always with us; it’s a part of our unfolding story, an everyday presence in the experience of life.

But if our memories are rewritten and our traumas recurring events, where does that leave the pursuit of truth? In today’s climate of fake news and disinformation, we hold truth on a higher pedestal than ever — a beacon of hope, justice, and decency in an often corrupt and self-serving world. And yet, despite our esteem of “the facts,” we readily accept that our own psyches, recollections, and internal lives are the product of distortions, edits, and embellishments. Where do we get off with this hypocrisy?

Maybe there’s some comfort in our double standards; they reveal how much we know that untrue stories can still convey important truths. And maybe treasuring what’s true over and above what’s factual is exactly what makes us human. AI expert Gary Marcus makes a telling point: Unlike AI, which can only hallucinate or “bullshit” because it doesn’t have a concept of truth, we can lie precisely because we believe in the existence of one.

“What can you be for if you are against authenticity?”

In this context, it’s curious that Merriam Webster’s Word of the Year for 2023 is “authentic.” Yes, we want everything to be “authentic,” to be “the real deal.” Authentic brands, authentic leaders, authentic social media posts, authentic art, authentic relationships — authenticity has become the prerequisite for trust. We want to bring our “authentic selves” to work and to life. We are repelled by people or things that seem scripted, staged, fabricated, or too slick.

But what is authenticity in the first place? You could say it’s the ultimate bastion of pure feeling — or even purity as a feeling itself. You could say it’s an important illusion of wholeness, intended to reveal an indiscernible truth. No matter how you describe authenticity, it’s going to sound noble and alluring. “What can you be for if you are against authenticity?” the psychoanalyst and essayist Adam Phillips asks.

But authenticity is not the same as truthfulness. Authenticity demands that something appears to be true by quasi-objective standards. It suggests that the emotions a person expresses align with what we believe to be their “true” intentions. Authenticity, thus, is a social construct: a consistent congruence of word and action based on carefully negotiated social conventions.

In reality, both truth and authenticity are impossible. There is no objective truth. We are all utterly inauthentic. We are exactly who we pretend to be, though we often have no clear notion of who that is. Our truth is constructed by overlapping untrue stories. The truth about us is constructed by other people. The truth about other people belongs to us, while their internal truth remains forever elusive. It all sounds a bit like an LSAT logic game.

Happy ending

But sometimes our truths meet. When you enter a conversation with another person — and, certainly, when you begin a relationship — you must loosen your grip on the truth. Meaningful engagement requires a partial relinquishing of your authoritative version of the world; you must let your truth collide with someone else’s, so that the pursuit of meaning becomes a shared one.

Phillips thinks that love cures us of our belief in authenticity. “The idea of authenticity is something we use to protect ourselves from love,” he writes. In his mind, love disabuses us of our fixation on truth, letting us write complex, meaningful, and contingent stories together.

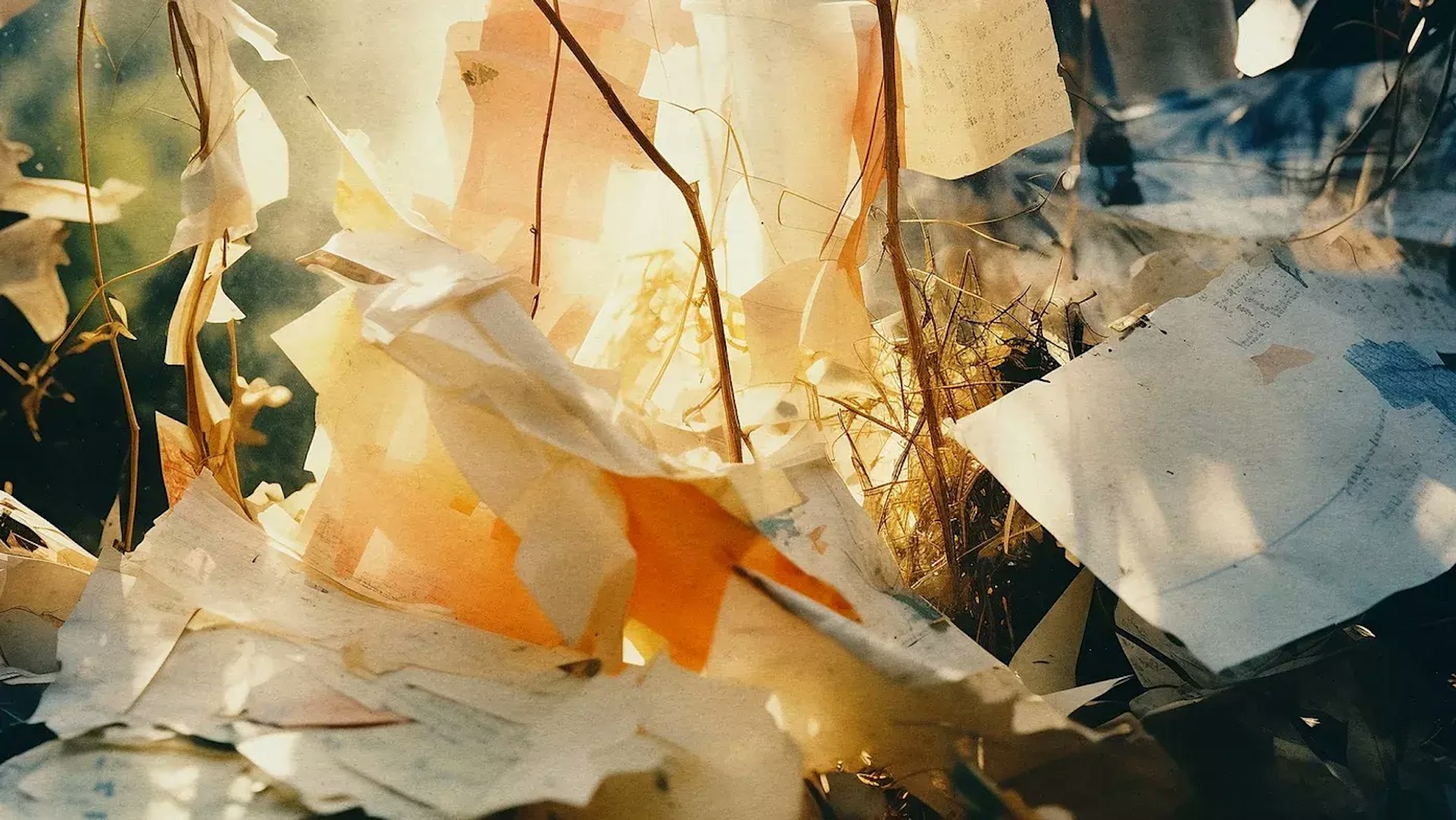

Our truth-making projects are unlikely to end any time soon — we’ll keep posting selfies, curating lists, retelling stories, and humble-bragging about our accomplishments, a vast cacophony of voices inflating or distorting our truths to prove our one-and-onlyness, trying to first overwrite our wounds and then our stories of them, adding layer after layer, revision after revision, until the whole project is like Greta Gerwig’s billion-dollar blockbuster Barbie: a muddled exaggeration replete with too much dialogue, too much text, too many plot points, too much drama.

In the end, life prevails over all those stories and reminds us of what it truly is: an attempt, an effort. An essay.

***

Wanted: Degrowth. Needed: Growth.